Published in Kai Tiaki: Nursing New Zealand 13.10 (Nov 2007): p20(2).

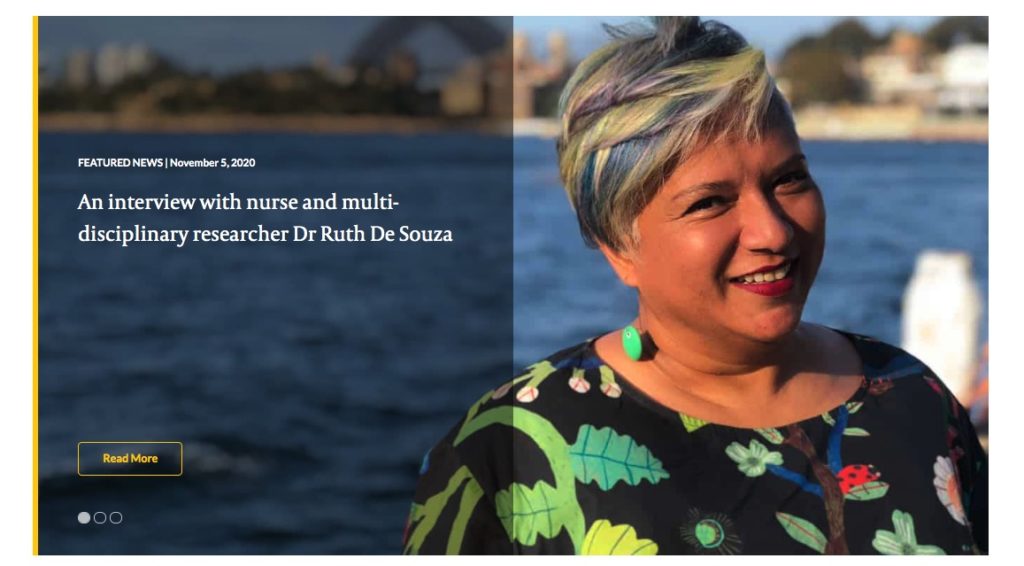

It is 11 years since my first conference presentation and I remember that day vividly. I had prepared carefully for the presentation; friends and family came to support me; but a tricky question at the end of my presentation took me by surprise: “Ruth, thanks for that interesting presentation. How does what you say relate to postmodemism?” I was mortified and fudged an answer. It’s a wonder that anyone presents realty! Why would you expose yourself in this way and what is the purpose of a presentation?

In this article I attempt to summarise some of my learning and share some strategies and ideas, in the hope of prompting readers to consider embracing the performance that is presenting. I am going to ask you first to think about who was the best speaker you have ever heard and what was good about them. Now, think about what presenting might have to offer you. Why should nurses think about presenting or public speaking? It is a good career move. The pay off is personal satisfaction, peer esteem and building your career. It is a good skill to develop–you might need to present research at a conference, in-house or at an interview. These experiences help you become a better presenter and increase your visibility.

Conferences, for example, provide an important arena and opportunity for people to exchange views and communicate with each other. They are also useful for linking up with the people who are most interested in your work.

What makes a good speaker?

What makes a good speaker? In my view, a good speaker begins and ends their presentation strongly; you are hooked from the first word to the last, by their brilliance, humour, wisdom, provocation and ability to entertain. They also know how to tell good stories, but they never read from their speech. They capture your attention because, not only do they know their own work, they also have a clear message.

So how does one go about speaking? I have developed as a presenter over the years from being flustered and over-prepared, to having far too much to say, to now beginning to feel natural and comfortable when I present at a conference or gathering of peers.

When I was a group therapist and facilitator, I had to speak to several people at a time and this helped me grow in confidence as a speaker. Then I was asked to facilitate a function attended by 250 people. This prompted me to do a Toastmasters course, where I learned how to recover from mistakes in a presentation. I also realised that when I was anxious, I lost my ability to be natural and humorous, but if I could manage my anxiety, then all would be well

In terms of conference presentations, I prepared by reading previous papers and began networking, so I got to know other people in my research field, which helped me realise I had something to offer.

Preparation crucial

Preparation is crucial to presenting well Three aspects need to be addressed: the purpose, structure and content of your presentation. In considering purpose, it is important to know the key messages you want to convey. It might help to start at the end and work backwards–every presentation needs a destination. Then consider what you need to say to assist the listener to get those key messages. Is there a context you need to introduce? How much can you assume your audience will know already? So to the structure. I tend to work on the basis of four parts to a presentation: the introduction, the body, the guts and the conclusion.

The purpose of the introduction is to motivate the audience, which you can do by having a warm up or a question. I also use this part to introduce myself and define the problem or issue, and set the scene. Then you can introduce the context, such as terminology and earlier work. At this point, I would also emphasise what your work contributes to the topic or area, and provide a road map of where your presentation is going. This normally takes around five minutes. The next part of the presentation outlines some big picture results or themes and why they are important. This is followed by the “guts” of what you want to say, where you present one key result, carefully and in-depth.

The conclusion is where many presenters (including myself) run out of steam. The conclusion involves rounding off your presentation neatly and linking everything you’ve said. This can be a good time to mention the weaknesses of your work, and it can help manage questions at the end. It is good to find a way to indicate the presentation is over. I do this by thanking the audience and asking if there are any questions.

Now to the content. Many people use PowerPoint presentations. Use slides like make up–sparingly and simply: common advice is don’t have too much on them; and don’t have too many. (I’m still working on this one.) Six words per bullet point and a maximum of six bullet points per slide is recommended.

The slides are merely an adjunct to your talk, so please don’t read them word for word (my pet hate). The purpose is to highlight key points for the audience and to prompt the speaker. In considering the number of slides to have, keep in mind that each slide takes about a minute and a hail or two minutes to read and fully understand?? If you have 87 slides for a 25-minute talk, like someone I was on a panel with recently, you are likely to overwhelm your audience. Take care with formatting your slides and make sure the spelling is correct. Lastly, be sure you’ve saved your presentation to two types of media. Practise your presentation, ask for a second opinion and get some feedback. Practising helps fine tune your timing.

On the day itself, make sure you are prepared and took and feet good. Ensure you take the media you are going to use and take a hard copy of the presentation to refer to. Say your presentation out loud. At the venue expect nothing to work and scope the technology. Address your anxiety. I do this by practising my presentation, going for a brisk walk and taking deep breaths. I also like to get to the venue early and mingle with those attending the conference, so I can develop some allies in the audience. Focus on being yourself and focus on giving.

Connecting with the audience

Now to the actual presentation. Make sure you project your voice to the very back of the room. It is important to know the audience and pitch your message accordingly. Make eye contact if possible–this is easier if you had time to meet people beforehand. Find a way to involve the audience and make sure you have a good opening. Use repetition to reinforce your message: tell them what you are going to tell them; tell them; then tell them what you told them, but repeat it in different ways. Make sore you are standing in the right place so you aren’t blocking your slides or other visual aids.

Remember that once you get involved in what you have to say, then the nervousness will go away. Don’t be afraid to pause, and you can pause for emphasis. If you get stuck, just move on to the next part of your presentation (others won’t notice). Be spontaneous, considerate and inclusive. I like to move around and I tend to focus on entertaining. If you can generously link in with what previous speakers have said, or affirm later speakers for continuity and reinforcement, that is all to the good. Whatever you do, don’t go over time.

Congratulations, you’ve finished. Now, let’s talk about feedback and questions. Feedback is critical to Learning how to improve your talk and for future presentations. Solicit feedback, if it isn’t freely given, but be prepared for some negative comments! Ask for written feedback, if appropriate.

Managing questions is important. Repeat the question so everyone can hear. It is important to be both prepared and polite. Keep your answers short where possible. If you get drawn into a Long discussion with a questioner, for the sake of your audience, offer to discuss the issue tater. Don’t be afraid to say that you don’t know. Find a way to turn criticism into a positive statement, eg “thanks for mentioning that, it’s given me something to think about”, rather than being defensive.

Different types of questions

In my experience there are four types of question: the genuine request; the selfish question (which is realty about the questioner saying “Look at me”); the malicious question (which is designed to expose you); and the question that has absolutely nothing to do with your presentation and makes you wonder if you and the questioner were in the same venue!

Presenting requires a delicate balance–preparation is important but so is being yourself and being spontaneous. It is important to have content and structure, but the more you have of both, the less room you have for questions and spontaneity. It is important to be inclusive, but be careful with humour and jokes or your own stories, unless you can Link them with your talk well. Lastly, be entertaining, know your material, keep it simple, be prepared, be creative and have fun!