“…the neo-liberal academy has compelled me to compete and compare, to work on my own, to overwork, and to count narrowly. At various times, neoliberal ideologies have crept into my mind/writing/body, breaking me down. The academy’s “finite games” of winners and losers, the demands to prove I am a “credible academic”, the narrow counting and the changing and hardening rules of entry have kept me running on the production treadmill, frequently distracting me from what matters most” (Harré et al., 2017, pp. 5, 9).

I am a serial book chapter reader and writer. If you check out this link, you’ll see I have written a fair few. Writing a book chapter seems less daunting than trying to write a whole book, and less prescriptive and intimidating than journal articles because I can more easily imagine the reader. It may be a student or someone from my academic or professional community, but I have a sense of their ethical and political commitments. In quantified academia, research activity and impact are crucial to academic promotion/tenure and research funding. In my field of health, peer-reviewed journal articles are the gold standard. When I think like a ‘professional’ academic I sometimes wonder if book chapters are ‘worth’ writing. So much of “successful” knowledge production depends on your discipline, your structural location (not only whether you are tenured or precarious, but also whether you have a marginalised identity/ies or work in a marginalised field), your preferences for dissemination or contribution in terms of who you write for, and how ambitious you are, so it’s political as well. None of this is helped by the ways in which academia is still predicated on being an exceptional competitive individual which can preclude more contemplative kinds of collaboration (Black, 2022). In the Gigiversity, there’s also what Mark Carrigan calls temporal budgeting which can be a barrier to writing as a creative process. Writing becomes calculated, something that has to be accounted for, and made time for.

I am not immune from living a calculated life. I recently said no to an invitation to write an academic book chapter (and I am still ambivalent about this) because of the opportunity cost, not because of wanting it published in a journal where it would “count” more, but because my career is now based on consulting, so the time I spend writing without payment means not getting paid. You can read more about the reasons not to write book chapters in this blog by Adam Chapnick. I have also co-edited a book Researching with Communities: Grounded perspectives on engaging communities in research, supposedly a huge no-no, but that’s for another blog. Rasmus Nielsen’s conceptualization of the value of the book chapter genre is helpful (1) argumentative chapters, (2) trailer chapters, and (3) review chapters. In the first category, a book chapter can help to think through an argument in an interpretive and personal way; and the second category where you operationalize the underlying concerns for another project is where my work has typically landed. I save the third for journal articles. So why even write book chapters? Here are some of my reasons.

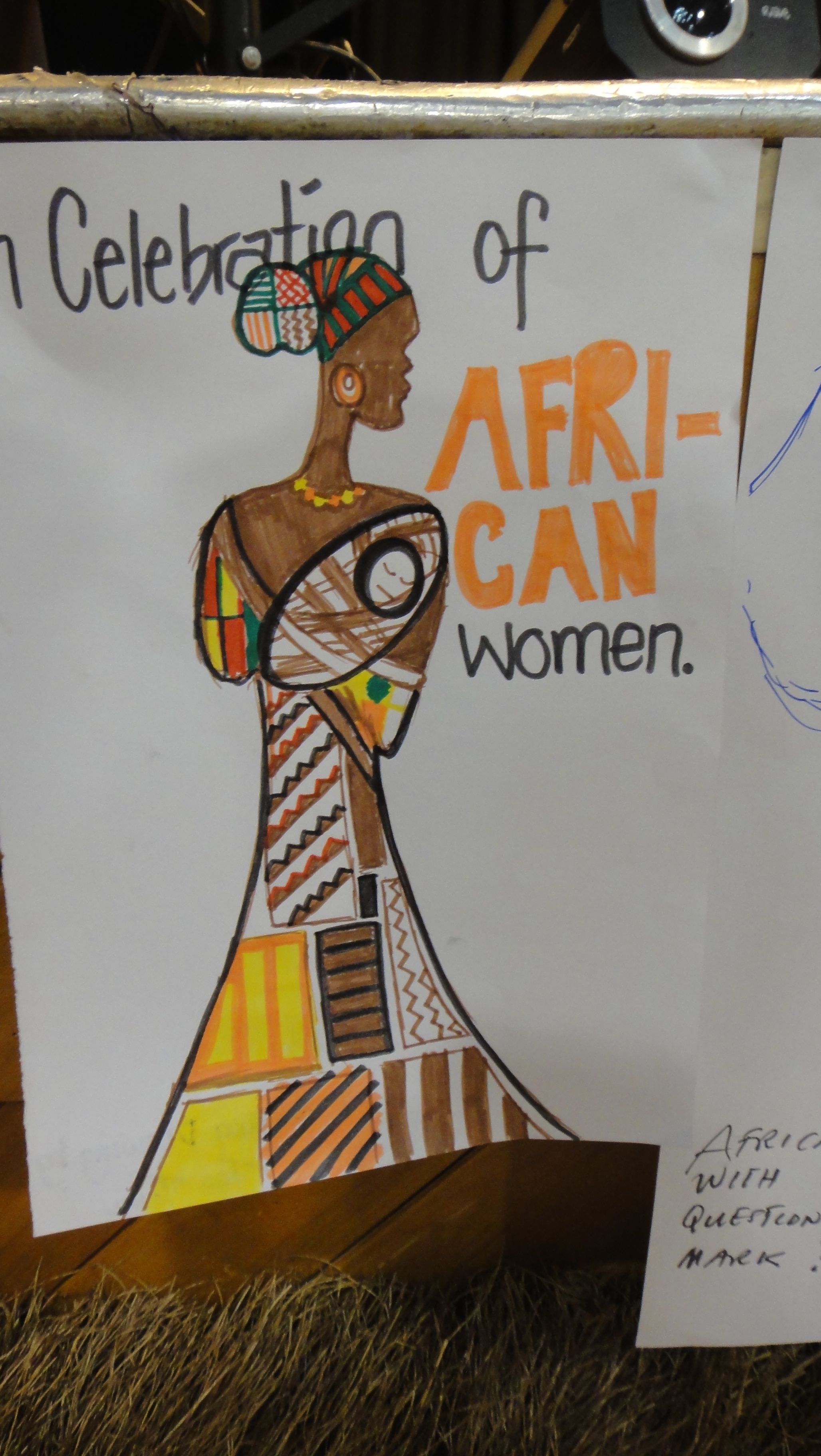

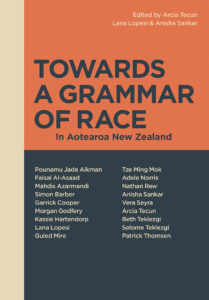

As a reader and scholar, anthologies have saved me as a person of color. This Bridge called my Back and later Black British Feminism edited by Heidi Mirza, which I devoured avidly in a largely monocultural academic New Zealand are just two examples. As an author Sara Ahmed, says that the Mirza book was pivotal to a broader political identity and that being part of “a collection can be to become a collective” (Ahmed, 2012, p.13). Younger me would have been so thrilled to get my hands on Towards a Grammar of Race In Aotearoa New Zealand edited by Arcia Tecun, Lana Lopesi and Anisha Sankar. Covering all the things younger me was living through but had no vocabulary for, things like racial capitalism, colonialism, white supremacy, and anti-Blackness.

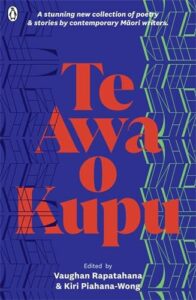

More elegantly and evocatively, my friend and podcast guest extraordinaire Alice Te Punga Somerville writing from Musqueam whenua, offers many metaphors for the collectivity of edited books, as food, as gathering, as connected across time and space, tantalising and replenishing. She adds (in discussing a new edited book by Kiri Piahana-Wong and Vaughan Rapatahana) “Māori have always been collective with our writing: so many anthologies, collections, joint readings, festivals, hui, organisations, writing groups, one-off collectives, roopu… this one draws consciously on the Into the World of Light/ Te Ao Mārama anthologies called into being by Ihimaera and others… but all of these Māori literary awa are part of a massive network of tributaries and streams and gorges and brooks and braided rivers and underwater culverts and, yes, all the way out to open ocean…she concludes “slurping down this awa which is replenishing and exciting me… and loving this hui with writers known by my heart, writers I have long admired from afar, and writers I have yet to meet.”

These relationships and collaborations are such a good reason for writing book chapters. Helen Kara who I enjoy for their interest in creative methods values the sense of community or social network that can accompany an edited book when there is a clear theme and the authors richly complement each other, which cannot be achieved with a single or co-authored book. It’s what Debra Brian says is a plus for the reader — “they often capture an important moment in the history of the discipline, or an opportunity to bring together multidisciplinary takes on a central theme.” I have recently had a chapter on racism and care published in No longer silent: Voices of 21st Century Nurses edited by Lesley Potter with support from the Australian College of Nursing. It is envisioned as a snapshot of contemporary nursing in Australia. Here’s a short excerpt:

There is trepidation and vulnerability that accompanies naming racism, rather than the more palatable good feeling word diversity (De Souza, 2018). Discourses of diversity and inclusion are what Ahmed (2012) describes as ‘non-performative institutional speech acts’ meaning that just their use as words do not necessarily change what it is they are naming Ahmed, 2012, p. 119). Racism is so direct, so harsh in the text as opposed to toned down with my good humor or the self-effacing charm I have cultivated as a bolster. I am a nurse who migrated to Australia post PhD for work in academia. As a person of color or brown settler, I occupy a position of unease and anxiety, uninvited living on stolen land, in a country where relationships between Indigenous people, settlers and migrants are contested. I am also privileged to be a mobile, highly educated researcher working in the prestigious context of a University. As (Moreton-Robinson, 2007, 2015) quips, the White nation-space of so-called Australia, excludes both Indigenous people and non-British people. However, I invoke this process of critical reflexivity and locate my own positionality to account for myself and for my writing. A person with ancestral heritage in Goa, India but whose personal and familiar multiple migrations, have been shaped by colonization. I provide these histories and geographies to account for how I write, they provide me with a specific set of ethical and political commitments that aim to contribute to making nursing a profession that is less discriminatory and more equitable for both those who follow me and those we purport to serve. I care about nurses and nursing and am troubled by the paradox that a profession that claims to care could be implicated in perpetuating inequities for some populations. This stance of critique and the desire for accountability may make what I write seem particularly critical, however, it also reflects a deep investment in the nursing profession.

Changes in models of publishing have also made writing book chapters more worthwhile Patrick Dunleavy says in an LSE blog. Dorothy Bishop admits her best writing is in book chapters where she has had the freedom to integrate broad perspectives, but argued in the past that writing a book chapter was like burying your work because of difficulties in trying to access and cite work. However, now that e-book chapters are becoming as discoverable, and more affordable, the reader or potential citer no longer has to pay massive prices for books that are just as easy to find as journal articles. Individual chapters have become easier to use in teaching, as they can be added to reading lists on learning management systems (LMS). I have added a book chapter on Cultural Safety I co-wrote for the book The Relationship is the Project for a lovely intensive course I’ve been teaching in the School of Art with Alan Hill and Jody Haines at RMIT University called Creative Practice in Place: Working on Unceded Lands. Interestingly the chapter has been reprinted online in two different contexts, in Arts Hub as Taking action for Cultural Safety and republished in Spotlight, the Arts Wellbeing Collective magazine which makes it more accessible. However, access does not equal citations, so even if they are used in essays or theses, they may not show up in citation metrics.

Book chapters open up different formats and creative options compared to journal articles, which is why one of my favorite academic bloggers Pat Thomson who blogs at Patter writes them. Another favorite blogger Agnes Bosanquet writes In defence of book chapters that book chapters let you publish “something experimental, fun and adventurous” and you can take more “risks with style, structure and method”. Concluding that “when I want to write in the company of others, flex my writing muscles in new ways, and find pleasure in the craft of writing, then book chapters are a gift”. Historian Zora Simic says “I find them a more liberating form than a journal article and some of that is because of the way I think – journal articles typically demand an argument that is pursued in coherent fashion whereas I prefer ambiguity, open and loose ends, experimentation, and exploration for the sake of it.” This desire to write playfully and creatively resonates with me. There’s also a pragmatic freedom that Thomson identifies. Firstly, because your chapter is part of a collection, you do not have to do as much prefacing and situating as you would in a journal article. and secondly, you do not have to convince people to read the chapter because the editors have already done that work for you.

Viewing a field through a different lens is another reason to write a book chapter, providing a way in which students or practitioners can get a feel for a topic, its scope and debates. Elaine Swan adds “I recommend them to students as they can see how a topic can be understood through different concepts and methods.” Scholars like Carol D’Cruz find the breadth of the approaches to tackling the same issue appealing: “I love variety in the perspective and approach in edited collections, especially when all answering the same/similar problem.” Some writers also appreciate the opportunity to learn, to use their experience in another context, like Zora Simic who says “Once I responded to a call for contributions to a book called Fat Sex. I’d always wanted to know more about the history of fat activism/feminism and this was the perfect opportunity. It had nothing whatsoever to do with my other research, apart from being about feminism. But I loved writing and researching it.”

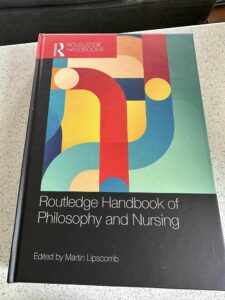

Leaving your mark in a field is another drawcard. Debra Brian contends saying yes to a book chapter “can signal your commitment and standing in the field, your academic social capital, etc — and it can bring other opportunities. Sometimes it is worth doing for the sake of collaboration and relationships and the opportunity to find a home for something that needs to be said but doesn’t really ‘fit’ in another format.” This really rang true for me in my contribution to Jessica Dillard-Wright’s book Nursing a Radical Imagination: Moving from Theory and History to Action and Alternate Futures co-edited with Jane Hopkins-Walsh and Brandon Brown where I wrote about creative methods in nursing education. We’ve subsequently collaborated on a number of other projects, Jess (and Jane) contributed an artwork for our exhibition and course for The Big Anxiety Festival, and did a Zoom guest lecture to art students. We have also just cowritten No as an act of care A glossary for kinship, care praxis, and nursing’s radical imagination Jessica Dillard-Wright, Favorite Iradukunda, Ruth De Souza, and Claire Valderama-Wallace in the tome Routledge Handbook of Philosophy and Nursing Edited By Martin Lipscomb. I feel deep gratitude for the friendship that has evolved between us in the process of talking and writing (a non-academic benefit (Tom Pepinsky) of writing book chapters)! Here’s the abstract:

Radical imagination and the transformations that ensue are fundamentally collaborative, connected, and conscious. In an effort to first imagine and then co-create a more just, equitable present/future for nursing and those with whom we care in the spirit of radical imagination, this chapter examines nursing care as praxis and the shifts that occur in embracing kinship as a reciprocal model for nursing. In so doing, we challenge embedded power structures within the healthcare-industrial complex – and thus nursing – as we currently know it. Using feminist, queer, anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, and abolitionist insights, we imagine a present/future for nursing liberated from the capitalist political economy entrenched in a boundless society of control. This speculative vision is urgent, encompassing, and material, bursting open the boundaries of nursing as we consider with whom we align and how we build toward a future on a deteriorating planet.

Obviously, academics have to be strategic about writing but I also write because writing helps me make sense of things. I write to think, just as I speak to think. The former is far more laborious for me but I am getting better at it. Book chapters allow me to play, to experiment, and to feel part of a community, a collective and that is hard to beat.