On 15 February 2016, I spoke on 612 ABC Brisbane Afternoons with Kelly Higgins-Devine about cultural appropriation and privilege. Our discussion was followed by discussion with guests: Andie Fox – a feminist and writer; Carol Vale a Dunghutti woman; and Indigenous artist, Tony Albert. I’ve used the questions asked during the interview as a base for this blog with thanks to Amanda Dell (producer).

Why has it taken so long for the debate to escape academia to be something we see in the opinion pages of publications now?

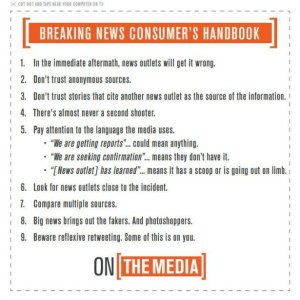

Social media and online activism have catapulted questions about identities and politics into our screen lives. Where television allowed us to switch the channel, or the topic skilfully changed at awkward moments in work or family conversations, our devices hold us captive. Simply scrolling through our social media feeds can encourage, enrage or mobilise us into fury or despair. Whether we like it or not, as users of social media we are being interpolated into the complex terrain of identity politics. Merely sharing a link on your social media feed locates you and your politics, in ways that you might never reveal in real time social conversations. ‘Sharing’ can have wide ranging consequences, a casual tweet before a flight resulted in Justine Sacco moving from witty interlocutor to pariah in a matter of hours. The merging of ‘private’ and public lives never being more evident.

How long has the term privilege been around?

The concept of privilege originally developed in relation to analyses of race and gender but has expanded to include social class, ability level, sexuality and other aspects of identity. Interestingly, Jon Greenberg points out that although people of color have fought racism since its inception, the best known White Privilege educators are white (Peggy McIntosh, Tim Wise and Robin DiAngelo). McIntosh’s 1988 paper White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences through Work in Women’s Studies extended a feminist analysis of patriarchal oppression of women to that of people of color in the United States. This was later shortened into the essay White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (pdf), which has been used extensively in a a range of settings because of it’s helpful list format .

Many people have really strong reactions to these concepts – why is that?

Robin DiAngelo, professor of multicultural education and author of What Does it Mean to Be White? Developing White Racial Literacy developed the term ‘white fragility’ to identify:

a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include outward display of emotions such as anger, fear and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence and leaving the stress-inducing situation

DiAngelo suggests that for white people, racism or oppression are viewed as something that bad or immoral people do. The racist is the person who is verbally abusive toward people of color on public transport, or a former racist state like apartheid South Africa. If you see yourself as a ‘good’ person then it is painful to be ‘called out’, and see yourself as a bad person. Iris Marion Young’s work useful. She conceptualises oppression in the Foucauldian sense as:

the disadvantage and injustice some people suffer not because of a tyrannical power coerces them but because of the everyday practices of a well-intentioned liberal society…

Young points out the actions of many people going about their daily lives contribute to the maintenance and reproduction of oppression, even as few would view themselves as agents of oppression. We cannot avoid oppression, as it is structural and woven throughout the system, rather than reflecting a few people’s choices or policies. Its causes are embedded in the unquestioned norms, habits, symbols and assumptions underlying institutional rules and the collective consequences of following those rules (Young, 1990). Seeing oppression as the practices of a well intentioned liberal society removes the focus from individual acts that might repress the actions of others to acknowledging that “powerful norms and hierarchies of both privilege and injustice are built into our everyday practices” (Henderson & Waterstone, 2008, p.52). These hierarchies call for structural rather than individual remedies.

We probably need to start with privilege – what does that term mean?

McIntosh identified how she had obtained unearned privileges in society just by being White and defined white privilege as:

an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I am meant to remain oblivious (p. 1).

Her essay prompted understanding of how one’s success is largely attributable to one’s arbitrarily assigned social location in society, rather than the outcome of individual effort.

“I got myself where I am today. Honestly, it’s not that hard. I think some people are just afraid of a little hard work and standing on their own two feet, on a seashell, on a dolphin, on a nymph-queen that are all holding them up.”

From: The Birth of Venus: Pulling Yourself Out Of The Sea By Your Own Bootstraps by Mallory Ortberg

McIntosh suggested that white people benefit from historical and contemporary forms of racism (the inequitable distribution and exercise of power among ethnic groups) and that these discriminate or disadvantage people of color.

How does privilege relate to racism, sexism? Are they the same thing?

It’s useful to view the ‘isms’ in the context of institutional power, a point illustrated by Sian Ferguson:

In a patriarchal society, women do not have institutional power (at least, not based on their gender). In a white supremacist society, people of color don’t have race-based institutional power.

Australian race scholars Paradies and Williams (2008) note that:

The phenomenon of oppression is also intrinsically linked to that of privilege. In addition to disadvantaging minority racial groups in society, racism also results in groups (such as Whites) being privileged and accruing social power. (6)

Consequently, health and social disparities evident in white settler societies such as New Zealand and Australia (also this post about Closing the gap) are individualised or culturalised rather than contextualised historically or socio-economically. Without context white people are socialized to remain oblivious to their unearned advantages and view them as earned through merit. Increasingly the term privilege is being used outside of social justice settings to the arts. In a critique of the Hottest 100 list in Australia Erin Riley points out that the dominance of straight, white male voices which crowds out women, Indigenous Australians, immigrants and people of diverse sexual and gender identities. These groups are marginalised and the centrality of white men maintained, reducing the opportunity for empathy towards people with other experiences.

Do we all have some sort of privilege?

Yes, depending on the context. The concept of intersectionality by Kimberlé Crenshaw is useful, it suggests that people can be privileged in some ways and not others. For example as a migrant and a woman of color I experience certain disadvantages but as a middle class cis-gendered, able-bodied woman with a PhD and without an accent (only a Kiwi one which is indulged) I experience other advantages that ease my passage through the world You can read more in the essay Explaining White Privilege to a Broke White Person.

How does an awareness of privilege change the way a society works?

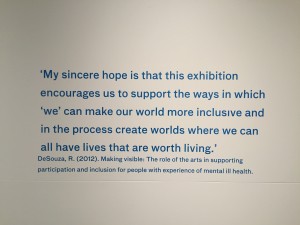

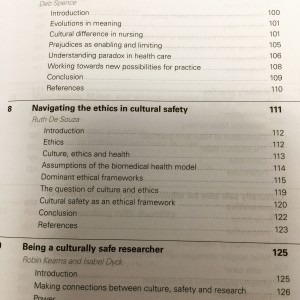

Dogs and Lizards: A Parable of Privilege by Sindelókë is a helpful way of trying to understand how easy it is not to see your own privilege and be blind to others’ disadvantages. You might have also seen or heard the phrase ‘check your privilege’ which is a way of asking someone to think about their own privilege and how they might monitor it in a social setting. Exposing color blindness and challenging the assumption of race-neutrality is one mechanism for addressing the issue of privilege and its obverse oppression. Increasingly in health and social care, emphasis is being placed on critiquing how our own positions contribute to inequality (see my chapter on cultural safety), and developing ethical and moral commitments to addressing racism so that equality and justice can be made possible. As Christine Emba notes “There’s no way to level the playing field unless we first can all see how uneven it is.” One of the ways this can be done is through experiencing exercises like the Privilege Walk which you can watch on video. Jenn Sutherland-Miller in Medium reflects on her experience of it and proposes that:

Instead of privilege being the thing that gives me a leg up, it becomes the thing I use to give others a leg up. Privilege becomes a way create equality and inclusion, to right old wrongs, to demand justice on a daily basis and to create the dialogue that will grow our society forward.

Is privilege something we can change?

If we move beyond guilt and paralysis we can use our privilege to build solidarity and challenge oppression. Audra Williams points out that a genuine display of solidarity can require making a personal sacrifice. Citing the example of Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, where in challenging the director of a commercial about the lack of women with speaking roles, he ends up not being in the commercial at all when it is re-written with speaking roles for women. Ultimately privilege does not gets undone through “confession” but through collective work to dismantle oppressive systems as Andrea Smith writes.

Cultural appropriation is a different concept, but an understanding of privilege is important, what is cultural appropriation?

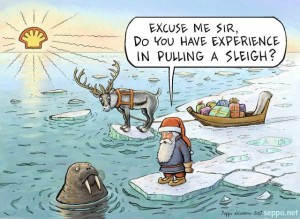

Cultural appropriation is when somebody adopts aspects of a culture that is not their own (Nadra Kareem Little). Usually it is a charge levelled at people from the dominant culture to signal power dynamic, where elements have been taken from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by the dominant group. Most critics of the concept are white (see white fragility). Kimberly Chabot Davis proposes that white co-optation or cultural consumption and commodification, can be cross-cultural encounters that can foster empathy and lead to working against privilege among white people. However, an Australian example of bringing diverse people together through appropriation backfired, when the term walkabout was used for a psychedelic dance party. Using a deeply significant word for initiation rites, for a dance party was seen as disrespectful. The bewildered organiser was accused via social media of cultural appropriation and changed the name to Lets Go Walkaround. So, I think that it is always important to ask permission and talk to people from that culture first rather than assuming it is okay to use.

What is the line between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation?

Maisha Z. Johnson cultural appreciation or exchange where mutual sharing is involved.

Can someone from a less privileged culture appropriate from the more privileged culture?

No, marginalized people often have to adopt elements of the dominant culture in order to survive conditions that make life more of a struggle if they don’t.

Does an object or symbol have to have some religious or special cultural significance to be appropriated?

Appropriation is harmful for a number of reasons including making things ‘cool’ for White people that would be denigrated in People of Color. For example Fatima Farha observes that when Hindu women in the United States wear the bindi, they are often made fun of, or seen as traditional or backward but when someone from the dominant culture wears such items they are called exotic and beautiful. The critique of appropriation extends from clothing to events Nadya Agrawal critiques The Color Run™ where you can:

run with your friends, come together as a community, get showered in colored powder and not have to deal with all that annoying culture that would come if you went to a Holi celebration. There are no prayers for spring or messages of rejuvenation before these runs. You won’t have to drink chai or try Indian food afterward. There is absolutely no way you’ll have to even think about the ancient traditions and culture this brand new craze is derived from. Come uncultured, leave uncultured, that’s the Color Run, promise.

The race ends with something called a “Color Festival” but does not acknowledge Holi. This white-washing (pun intended) eradicates everything Indian from the run including Holi, Krishna and spring. In essence as Ijeoma Oluo points out cultural appropriation is a symptom, not the cause, of an oppressive and exploitative world order which involves stealing the work of those less privileged. Really valuing people involves valuing their culture and taking the time to acknowledge its historical and social context. Valuing isn’t just appreciation but also considering whether the appropriation of intellectual property results in economic benefits for the people who created it. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar suggests that it is often one way:

One very legitimate point is economic. In general, when blacks create something that is later adopted by white culture, white people tend to make a lot more money from it… It feels an awful lot like slavery to have others profit from your efforts.

Loving burritos doesn’t make someone less racist against Latinos. Lusting after Bo Derek in 10 doesn’t make anyone appreciate black culture more… Appreciating an individual item from a culture doesn’t translate into accepting the whole people. While high-priced cornrows on a white celebrity on the red carper at the Oscars is chic, those same cornrows on the little black girl in Watts, Los Angeles, are a symbol of her ghetto lifestyle. A white person looking black gets a fashion spread in a glossy magazine; a black person wearing the same thing gets pulled over by the police. One can understand the frustration.

The appropriative process is also selective, as Greg Tate observes in Everything but the burden, where African American cultural properties including music, food, fashion, hairstyles, dances are sold as American to the rest of the world but with the black presence erased from it. The only thing not stolen is the burden of the denial of human rights and economic opportunity. Appropriation can be ambivalent, as seen in the desire to simultaneously possess and erase black culture. However, in the case of the appropriation of the indigenous in the United States, Andrea Smith declares (somewhat ironically), that the desire to be “Indian” often precludes struggles against genocide, or demands for treaty rights. It does not require being accountable to Indian communities, who might demand an end to the appropriation of spiritual practices.

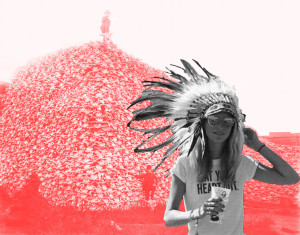

Go West – Black: Random Coachella attendee, 2014. Red: Bison skull pile, South Dakota, 1870’s by Roger Peet.

Some people believe the cuisines of other cultures have been appropriated – is this an extreme example, or is it something we should consider?

The world of food can be such a potent site of transformation for social justice. I am a committed foodie (“somebody with a strong interest in learning about and eating good food who is not directly employed in the food industry” (Johnston and Baumann, 2010: 61). I am also interested in the politics of food. I live in Melbourne, where food culture has been made vibrant by the waves of migrants who have put pressure on public institutions, to expand and diversify their gastronomic offerings for a wider range of people. However, our consumption can naturalise and make invisible colonial and racialised relations. Thus the violent histories of invasion and starvation by the first white settlers, the convicts whose theft of food had them sent to Australia and absorbed into the cruel colonial project of poisoning, starving and rationing indigenous people remain hidden from view. So although we might love the food we might not care about the cooks at all as Rhoda Roberts Director of the Aboriginal Dreaming festival observed in Elspeth Probyn’s excellent book Carnal Appetites:

In Australia, food and culinary delights are always accepted before the differences and backgrounds of the origin of the aroma are.

Lee’s Ghee is an interesting example of appropriation, she developed an ‘artisanal’ ghee product, something that has been made for centuries in South Asia.

Lee Dares was taking the fashion world by storm working as a model in New York when she realized her real passion was elsewhere. So, she made the courageous decision to quit her glamorous job and take some time to explore what she really wanted to do with her life. Her revelation came after she spent some time learning to make clarified butter, or ghee, on a farm in Northern India. Inspired, she turned to Futurpreneur Canada to help her start her own business, Lee’s Ghee, producing unique and modern flavours of this traditional staple of Southeast Asian cuisine and Ayurvedic medicine.

The saying “We are what we eat” is about not only the nutrients we consume but also to beliefs about our morality. Similarly ‘we’ are also what we don’t eat, so our food practices mark us out as belonging or not belonging to a group.So, food has an exclusionary and inclusionary role with affective consequences that range from curiosity, delight to disgust. For the migrant for example, identity cannot be taken for granted, it must be worked at to be nurtured and maintained. It becomes an active, performative and processual project enacted through consumption. With with every taste, an imagined diasporic group identity is produced, maintained and reinforced. Food preparation represents continuity through the techniques and equipment that are used which affirm family life, and in sharing this food hospitality, love, generosity and appreciation can be expresssed. However, the food that is a salve for the dislocated, lonely, isolated migrant also sets her apart, making her stand out as visibly, gustatorily or olfactorily different. The resource for her well being also marks her as different and a risk. If her food is seen as smelly, distasteful, foreign, violent or abnormal, these characteristics can be transposed to her body and to those bodies that resemble her. Dares attempt to reproduce food that is made in many households and available for sale in many ‘ethnic’ shops and selling it as artisanal, led to accusations of ‘colombusing’ — a term used to describe when white people claim they have discovered or made something that has a long history in another culture. Also see the critique by Navneet Alang in Hazlitt:

The ethnic—the collective traditions and practices of the world’s majority—thus works as an undiscovered country, full of resources to be mined. Rather than sugar or coffee or oil, however, the ore of the ethnic is raw material for performance and self-definition: refine this rough, crude tradition, bottle it in pretty jars, and display both it and yourself as ideals of contemporary cosmopolitanism. But each act of cultural appropriation, in which some facet of a non-Western culture is columbused, accepted into the mainstream, and commodified, reasserts the white and Western as norm—the end of a timeline toward which the whole world is moving.

If this is the first time someone has heard these concepts, and they’re feeling confused, or a bit defensive, what can they do to understand more about it?

Here are some resources that might help, videos, illustrations, reading and more.

White privilege

- Toby Morris has created a beautiful illustration of Privilege.

- A hilarious look at white male privilege by Elliot Kalan.

- Video White privilege glasses from Chicago Theological Seminar.

- 11 Common Ways White Folks Avoid Taking Responsibility for Racism in the US by Robin DiAngelo.

- A great edited book on whiteness in Australia: Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism By Aileen Moreton-Robinson

- McSweeney’s have some hilarious writing on privilege including: a humorous product review of the invisible backpack of white privilege from by Joyce Miller; Don’t worry, I checked my privilege by Elliot Kalan; Some relatively recent College grads discuss their maids by Ellie Kemper and Privilege-checking preambles of varying degrees of singularity by George Morony.

- 4 Ways White People Can Process Their Emotions Without Bringing the White Tears by Jennifer Loubriel.

- The fairest — and funniest — way to split a restaurant bill by Emily Badger·

- See the excellent work on privilege by the Whariki Research Group, Massey University, New Zealand.

- Read about the reductive seduction of other people’s problems.

- Read more about whiteness, in an interview with Robin DiAngelo.

- Tim Wise has tons of resources.

- Check your privilege at the door.

- View the Unequal Opportunity Race. Screened as part of the Black History Month program at Glen Allen High School in Glen Allen, Virginia.

- This piece by Ali Owens about 4 problematic statements White people make about race — and what to say instead is useful: “I Don’t See Color.” “All Lives Matter.” “If racism is still a problem, how come we have a black president?” “Reverse racism is real.”

- The eight ways of being white by Gillian Schutte examines Barnor Hesses’ work (about whiteness studies from a radical black perspective) outlining the eight categories of white identity.

- An interesting read about privilege in sport using the example of Maria Sharapova and Serena Williams: The Benefit of the Doubt: A Case Study On White Privilege.

- Whiteness as Metaprivilege.

- The Subtle Linguistics of Polite White Supremacy.

- If you’d like to try the group exercise on privilege adapted from the Horatio Alger exercise by Ellen Bettman, you can read the questions here.

- Oscar Kightley’s terrific take down of the myth of Maori privilege.

- Brown eye asking about whether Maori seats in New Zealand is privileging Maori.

- A sobering read Death by gentrification: the killing that shamed San Francisco | Rebecca Solnit.

Cultural appropriation

- Aarti Olivia has a lovely piece on when it is appropriate to wear Indian cultural items.

- An exploration of Orientalism & Asian cultural appropriation as found in American music by Ube Empress.

- A much-needed primer on cultural appropriation by Katie J.M. Baker.

- More about food and cultural appropriation by Niya Bajaj.

- Check out this exploration of visual and auditory appropriation in US culture by Portland artist Roger Peet, featuring local residents.

- A critique of appropriation in fashion, Valentino’s African summer in Parallel magazine.

- I’ve written about cultural consumption in this piece on food and festivals, also about the white saviour complex and moving from being a bystander to an ally.

- A useful explanation on the meaning of a Native American headdress and why not to wear one.

- Brilliant piece by Texta Queen on cultural appropriation, white privilege and art on the fabulous Peril site.