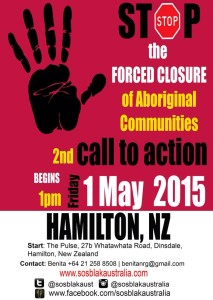

The view expressed by Tony Abbott (Prime Minister and the Minister for Indigenous Affairs), that taxpayers shouldn’t be expected to fund the “lifestyle choices” of Aboriginal people living in remote regions in support of Colin Barnett’s (West Australian Premier) decision to close 150 remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia reflects the repetition of the colonial project and Aboriginal dispossession. One of the mythologies of a white settler society is that white people are the first to arrive and develop the land, with colonisation a benign force (rather than one enacted through the processes of conquest and genocide and displacing the indigenous (Razack, 2002)). Closing the community draws attention away from governmental failures to ‘Close the Gap’ and instead displaces the blame on the supposed inadequacies and problems of Aboriginal communities (Amy McQuire) thereby individualising socio-political inequalities rather than revealing them as historic and structural. The paternalism of closing the communities “for their own good” and for the common good, appears benign but hides the brutality of forced removal and in doing so denies the significance of indigeneity as Mick Dodson notes:

It is not a “lifestyle choice” to be be born in and live in a remote Aboriginal community. It is more a decision to value connection to country, to look after family, to foster language and celebrate our culture. There are significant social, environmental and cultural benefits for the entire nation that flow from those decisions.

The protests against this cruel action have resounded around the world and have resonated in Aotearoa where I have lived for most of my life although I now live in the lands of the Kulin Nations in Gippsland as a migrant. As a nurse educator and researcher I am shaped by colonialism’s continuing effects in the white settler nation of Australia.

Nurses have often played an important part in social justice. Recently nursing professional bodies made a stand against violent state practices with the Australian College of Nursing (ACN) and Maternal Child and Family Health Nurses Australia (MCaFHNA) supporting The Forgotten Children report by the Australian Human Rights Commission against detaining children in immigration detention centres. Others like Chris Wilson wrote in Crikey about the many limitations of the Northern Territory Intervention:

I am saddened that the intervention has wasted so many resources, given so little support or recognition to the workers on the ground, paid so little attention to years of reports and above all involved absolutely no consultation with anyone, especially community members. The insidious effect of highlighting child abuse over all the other known problems in Aboriginal health is destructive to male health, mental health and community health, is unfounded in fact and is based in the inherent ignorance of this racist approach.

It has made me think about how nurses and midwives don’t often problematise our locations and consider our responsibilities within a social context of the discursive and material legacies of colonialism, neoliberalism, austerity and ‘othering’ (of Muslims, of refugees of Indigenous people) and “the ways in which we are complicitous in the subordination of others” (Razack, 1998, p.159). As Razack notes, groups that see themselves as apolitical must call into question their roles as “innocent subjects, standing outside of hierarchical social relations, who are not accountable for the past or implicated in the future” (Razack, 1998, p.10).

Colonisation and racism have been unkind to Indigenous people (term often used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples) with the health status of Indigenous people often compared to that of a developing country as I have pointed out elsewhere. The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage 2014 report measures the wellbeing of Australia’s Indigenous peoples. Briefly, Indigenous people:

- Experience social and health inequalities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2004).

- Are over represented and experience a higher burden of disease and higher mortality at younger ages than non-Indigenous Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012b).

So, the question for me as a researcher and educator are what responsibility do nurses and the discipline of nursing have to Aboriginal health?

1) Recognise colonisation as a determinant of health

Indigenous people enjoyed better health in 1788 than people in Europe, they had autonomy over their lives, (ceremonies, spiritual practices, medicine, social relationships, management of land, law, and economic activities), but also didn’t suffer from illnesses that were endemic in18th century Europe. They didn’t have smallpox, measles, influenza, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, venereal syphilis and gonorrhoea. However, they were known to have suffered from; hepatitis B; some bacterial infections; some intestinal parasites; trauma; anaemia; arthritis; periodontal disease; and tooth attrition.

What’s often difficult for many nurses and students to imagine is that the past could have anything to do with the present, however, research in other settler colonial societies shows a clear relationship between social disadvantages experienced by Indigenous people and current health status. Colonisation and the spread of non-Indigenous peoples saw the introduction of illness (eg smallpox); the devaluing of culture; the destruction of traditional food base; separation from families; dispossession of whole communities. Furthermore, the ensuing loss of autonomy undermined social vitality, reduced resilience and created dispossession, demoralisation and poor health.

The negative impacts of colonisation on Indigenous led colonial authorities to try to ‘protect’ remaining Indigenous peoples, which saw the establishment of Aboriginal ‘protection’ boards (the first established in Victoria by the Aboriginal Protection Act of 18690. However, ‘protection’ imposed enormous restrictions eg living in settlements; forced separation of Indigenous children from their families. With between one-in-three and one-in-ten Indigenous children forcibly removed from their families and communities from 1910 until 1970. The result was irrevocable harm as one of the Stolen Generations stated:

We may go home, but we cannot relive our childhoods. We may reunite with our mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, aunties, uncles, communities, but we cannot relive the 20, 30, 40 years that we spent without their love and care, and they cannot undo the grief and mourning they felt when we were separated from them

For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry. To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry. And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.

Also watch Babakiueria which uses role reversal to satirise and critique Australia’s treatment of its Indigenous peoples. Aboriginal actors play the colonisers, while white actors play the indigenous Babakiuerians.

2) Recognise continuing colonial practices

This blog started with the news of the closures of 150 remote Aboriginal communities in WA. Only one example of continuing colonial practices. Mick Dodson suggests that the closure of the 150 WA communities reflects an inability of the descendants of settlers to:

negotiate in a considered way the right of Aboriginal people to live as Aboriginal peoples in our own lands and seas, while also participating in every aspect of life as contemporary Australian citizens.

You can also read about proposed alternatives to the closure by Rebecca Mitchell.

3) Develop an understanding of racism as a determinant of health

Racism (racial discrimination) is linked with colonisation and oppression and is a social determinant of health. Nancy Krieger (2001) defines it as a process by which members of a socially defined racial group are treated unfairly because of membership of that group. Too often racism is seen as individual actions rather than as structural and embedded as this video shows. We know that racism damages health and in the health sector health systems and service providers can perpetuate Aboriginal health care disparities through attitudes and practices (Durey).

Anti-racist scholars suggest that there are three levels of racism in health.

- Institutional: Practices, policies or processes experienced in everyday life which maintain and reproduce avoidable and unfair inequalities across ethnic/racial groups (also called systemic racism);

- Interpersonal, in interactions between individuals either within their institutional roles or as private individuals;

- Internalised, where an individual internalises attitudes, beliefs or ideologies about the inferiority of their own group.

Krieger and others have written extensively about how racism affects health. People who experience racism experience the following:

- Inequitable and reduced access to the resources required for health;

- Inequitable exposure to risk factors associated with ill-health;

- Stress and negative emotional/cognitive reactions which have negative impacts on mental health as well as affecting the immune, endocrine, cardiovascular and other physiological systems;

- Engagement in unhealthy activities and disengagement from healthy activities

1 in 3 Aboriginal Victorians experienced racism in a health care setting according to a VicHealth survey. The respondents reported:

- Poorer health status;

- Lower perceived quality of care;

- Under-utilisation of health services;

- Delays in seeking care;

- Failure to follow recommendations;

- Societal distrust;

- interruptions in care;

- Mistrust of providers;

- Avoidance of health care systems.

This video on understanding the impact of racism on Indigenous child health by Dr Naomi Priest is well worth a look.

4) Develop a collective understanding of health and the importance of cultural determinants of health

Health is defined in the National Aboriginal Health Strategy (1989) as:

Not just the physical well-being of the individual but the social, emotional and cultural well-being of the whole community. This is a whole of life view and it also includes the cyclical concept of life-death-life

It is important that in considering the issues of colonisation, racism and inter-generational trauma that the diverse cultures and histories of indigenous people are not viewed through a deficit lens. So often mainstream media reinforce the myth that responsibility for poor health (whether it’s about people who drink, are obese or smoke) is an individual and group one rather than linked with social determinants including colonisation, economic restructuring or the devastating social consequences of state neoliberal policies. As Professor Ngiare Brown notes, there are significant cultural determinants of health which should be supported including:

- Self-determination; Freedom from discrimination;

- Individual and collective rights;

- Freedom from assimilation and destruction of culture;

- Protection from removal/relocation;

- Connection to, custodianship, and utilisation of country and traditional lands;

- Reclamation, revitalisation, preservation and promotion of language and cultural practices;

- Protection and promotion of Traditional Knowledge and Indigenous Intellectual Property; and

- Understanding of lore, law and traditional roles and responsibilities.

5) Develop an understanding of the organisations, policies, levers and strategies that are available to support Indigenous wellbeing

- Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs), which are primary health care services operated by local Aboriginal communities to deliver holistic, comprehensive, and culturally appropriate health care. There are over 150 ACCHSs in urban, regional and remote Australia.

- Close the gap campaign targets (also see a recent blogpost) developed by a consortium of 40 of Australia’s leading Indigenous and non-Indigenous health peak bodies and human rights organisations, which calls on Australian governments to commit to achieving Indigenous health equality within 25 years.

- 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 24 of which points out that Indigenous people have the right “to access, without any discrimination, [to] all social and health services” and “have an equal right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. States shall take the necessary steps with a view to achieving progressively full realisation of this right”.

- Become familiar with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-2023.

- Support the WHO Closing the gap in a generation, which recommends three actions for improving the world’s health:

- Improve the conditions of daily life – the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.

- Tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources – the structural drivers of those conditions of daily life – globally, nationally, and locally.

- Measure the problem, evaluate action, expand the knowledge base, develop a workforce that is trained in the social determinants of health, and raise public awareness about the social determinants of health.

In recognising the linkages and operational relationships that exist between health and human rights, the nursing profession respects the human rights of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the traditional owners of this land, who have ownership of and live a distinct and viable culture that shapes their world view and influences their daily decision making. Nurses recognise that the process of reconciliation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-indigenous Australians is rightly shared and owned across the Australian community. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, while physical, emotional, spiritual and cultural wellbeing are distinct, they also form the expected whole of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander model of care

6) Becoming a critical, reflexive, knowledgeable nurse who legitimates the cultural rights, values and expectations of Aboriginal people

More than ever, social justice provides a valuable lens for nursing practice (see Sir Michael Marmot’s speech). Cultural competence and safety directly reduce health disparities experienced by Indigenous Australians (Lee et al., 2006; Durey, 2010). It makes sense that the safer the health care system and its workers are, the more likely Indigenous people are to engage and use the services available. Early engagement in the health care system results in early health intervention strategies, prevention of illness and improved overall health outcomes for Indigenous Australians. The key features of cultural competence identified in the Cultural diversity plan for Victoria’s specialist mental health services 2006-2010 are:

- Respectful and non-judgemental curiosity about other cultures, and the ability to seek cultural knowledge in an appropriate way;

- Tolerance of ambiguity and ability to handle the stress of ambiguous situations;

- Readiness to adapt behaviours and communicative conventions for intercultural communication.

Nurses have a role in improving health outcomes, but this requires an understanding of the reasons why there are higher morbidity and mortality rates in Indigenous populations than in the general population. It requires that nurses engage in reflection and interrogate the existing social order and how it reproduces discriminatory practices in structural systems such as health care, in institutions and in health professionals (Durey, 2010). It’s important that as nurses we focus on our own behaviour, practice and skills both as professionals and individuals working in the health system.

I think this statement about Cultural security from the Department of Health, Western Australian Health (2003) Aboriginal Cultural Security: A background paper, page 10. is a valuable philosophy of practice:

Commitment to the principle that the construct and provision of services offered by the health system will not compromise the legitimate cultural rights, values and expectations of Aboriginal people. It is a recognition, appreciation and response to the impact of cultural diversity on the utilisation and provision of effective clinical care, public health and health system administration

To conclude, I leave the last words to Professor Ngiare Brown:

We represent the oldest continuous culture in the world, we are also diverse and have managed to persevere despite the odds because of our adaptability, our survival skills and because we represent an evolving cultural spectrum inclusive of traditional and contemporary practices. At our best, we bring our traditional principles and practices – respect, generosity, collective benefit, collective ownership- to our daily expression of our identity and culture in a contemporary context. When we are empowered to do this, and where systems facilitate this reclamation, protection and promotion, we are healthy, well and successful and our communities thrive.

References

Universities of Australia. (2011). National best practice framework for indigenous cultural competency in Australian Universities.

Awofeso, N. (2011). Racism: A major impediment to optimal indigenous health and health care in Australia. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, 11(3), 1-8.

Best, O., & Stuart, L. (2014). An Aboriginal nurse-led working model for success in graduating indigenous Australian nurses. Contemporary Nurse, 4082-4101.

Chapman, R., Smith, T., & Martin, C. (2014). Qualitative exploration of the perceived barriers and enablers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people accessing healthcare through one victorian emergency department. Contemporary Nurse.

Christou, A., & Thompson, S. C. (2012). Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes and behavioural intention among indigenous western Australians. BMC Public Health, 12, 528. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-528

Downing, R., & Kowal, E. (2010). Putting indigenous cultural training into nursing practice. Contemporary Nurse, 37(1), 10-20. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.010

Durey, A. (2010). Reducing racism in Aboriginal health care in Australia: Where does cultural education fit? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 34 Suppl 1, S87-92. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00560.x

Durey, A., Lin, I., & Thompson, D. (2013). It’s a different world out there: Improving how academics prepare health science students for rural and indigenous practice in Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(5), 722-733.

Haynes, E., Taylor, K. P., Durey, A., Bessarab, D., & Thompson, S. C. (2014). Examining the potential contribution of social theory to developing and supporting Australian indigenous-mainstream health service partnerships. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 75. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0075-5

Herk, K. A. V., Smith, D., & Andrew, C. (2014). Identity matters: Aboriginal mothers’ experiences of accessing health care. Contemporary Nurse. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.057

Hunt, L., Ramjan, L., McDonald, G., Koch, J., Baird, D., & Salamonson, Y. (2015). Nursing students’ perspectives of the health and healthcare issues of Australian indigenous people. Nurse Education Today, 35(3), 461-7. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2014.11.019

Kelly, J., West, R., Gamble, J., Sidebotham, M., Carson, V., & Duffy, E. (2014). ‘She knows how we feel’: Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childbearing women’s experience of continuity of care with an Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander midwifery student. Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 27(3), 157-62. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2014.06.002

Kildea, S., Kruske, S., Barclay, L., & Tracy, S. (2010). Closing the gap: How maternity services can contribute to reducing poor maternal infant health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Rural and Remote Health, 10(1383), 9-12.

Kowal, E. (2008). The politics of the gap: Indigenous Australians, liberal multiculturalism, and the end of the self-determination era. American Anthropologist, 110(3), 338-348.

Larson, A., Gillies, M., Howard, P. J., & Coffin, J. (2007). It’s enough to make you sick: The impact of racism on the health of Aboriginal Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 31(4), 322-329.

Liaw, S. T., Lau, P., Pyett, P., Furler, J., Burchill, M., Rowley, K., & Kelaher, M. (2011). Successful chronic disease care for Aboriginal Australians requires cultural competence. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 35(3), 238-48. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00701.x

Nash, R., Meiklejohn, B., & Sacre, S. (2006). The Yapunyah project: Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in the nursing curriculum. Contemporary Nurse, 22(2), 296-316. doi:10.5172/conu.2006.22.2.296

Nielsen, A. M., Stuart, L. A., & Gorman, D. (2014). Confronting the cultural challenge of the whiteness of nursing: Aboriginal registered nurses’ perspectives. Contemporary Nurse, 48(2), 190-6. doi:10.5172/conu.2014.48.2.190

Paradies, Y. (2005). Anti-Racism and indigenous Australians. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 5(1), 1-28.

Paradies, Y., & Cunningham, J. (2009). Experiences of racism among urban indigenous Australians: Findings from the DRUID study. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(3), 548-573. doi:10.1080/01419870802065234

Paradies, Y., Harris, R., & Anderson, I. (2008). The impact of racism on indigenous health in Australia and aotearoa: Towards a research agenda. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health Darwin.

Pedersen, A., Beven, J., Walker, I., & Griffiths, B. (2004). Attitudes toward indigenous Australians: The role of empathy and guilt. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 14(4), 233-249. doi:10.1002/casp.771

Pedersen, A., Dudgeon, P., Watt, S., & Griffiths, B. (2006). Attitudes toward indigenous Australians: The issue of special treatment. Australian Psychologist, 41(2), 85-94. Pijl-Zieber, E. M., & Hagen, B. (2011). Towards culturally relevant nursing education for Aboriginal students. Nurse Education Today, 31(6), 595-600. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.014Prior, D. (2009). The meaning of cancer for Australian Aboriginal women; changing the focus of cancer nursing. European Journal of Oncology Nursing : The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 13(4), 280-6. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2009.02.005

Rigby, W., Duffy, E., Manners, J., Latham, H., Lyons, L., Crawford, L., & Eldridge, R. (2010). Closing the gap: Cultural safety in indigenous health education. Contemporary Nurse, 37(1), 21-30. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.021

Rix, E. F., Barclay, L., Wilson, S., & Barclay, E. R. L. (2014). Can a white nurse get it?Reflexive practiceand the non-indigenous clinician/researcher working with Aboriginal people. Rural Remote Health, 4, 2679.

Stuart, L., & Nielsen, A. -M. (2014). Two Aboriginal registered nurses show us why black nurses caring for black patients is good medicine. Contemporary Nurse. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.096

Szoke, H. (2012). National anti-racism strategy. Australian Human Rights Commission.

Thackrah, R. D., & Thompson, S. C. (2014). Confronting uncomfortable truths: Receptivity and resistance to Aboriginal content in midwifery education. Contemporary Nurse. doi:10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.113

Thackrah, R. D., Thompson, S. C., & Durey, A. (2014). “Listening to the silence quietly”: Investigating the value of cultural immersion and remote experiential learning in preparing midwifery students for clinical practice. BMC Research Notes, 7, 685. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-685

Williamson, M., & Harrison, L. (2010). Providing culturally appropriate care: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(6), 761-9. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.012

Ziersch, A. M., Gallaher, G., Baum, F., & Bentley, M. (2011a). Responding to racism: Insights on how racism can damage health from an urban study of Australian Aboriginal people. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 73(7), 1045-53. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.058