Unpublished manuscript for those who might be interested. Cite as: DeSouza, R. (2016, July 16). Using forum theatre to facilitate reflection and culturally safe practice in nursing [Web log post]. Retrieved from: http://ruthdesouza.dreamhosters.com/2016/07/16/using-forum-theatre-for-reflective-practice/

High quality communication is central to nursing practice and to nurse education. The quality of interaction between service users/patients and inter-professional teams has a profound impact on perception of quality of care and positive outcomes. Creating spaces where reflective practice is encouraged allows students to be curious, experiment safely, make mistakes and try new ways of doing things. Donald Schon (1987) likens the world of professional practice to terrain made up of high hard ground overlooking a swamp. Applying this metaphor in Nursing, Street (1991) contends that some clinical problems can be resolved through theory and technique (on hard ground), while messy, confusing problems in swampy ground don’t have simple solutions but their resolution is critical to practice.

Rocks Philip Island

Australian society has an Indigenous foundation and is becoming increasingly multicultural.In Victoria 26.2 percent of Victorians and 24.6 per cent of Australians were born overseas, compared with New Zealand (22.4 per cent), Canada (21.3 per cent), United States (13.5 per cent) and The United Kingdom (10.4 per cent). Australia’s multicultural policy allows those who call Australia home the right to practice and share in their cultural traditions and languages within the law and free from discrimination (Australia Government, 2011, p. 5). Yet, research highlights disparities in the provision of health care to Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) groups and health services are not always able to ensure the delivery of culturally safe practice within their organisations (Johnstone & Kanitsaki, 2008).

An important aspect of cultural safety is the recognition that the health care system has its own culture. In Australia, this culture is premised on a western scientific worldview. Registered nurses (RNs) have a responsibility to provide culturally responsive health care that is high quality, safe, equitable and meets the standards expected of the profession such as taking on a leadership role, being advocates and engaging in lifelong learning. RNs who practice with cultural responsiveness are able to ‘respond to the healthcare issues of diverse communities’ (Victorian Department of Health [DoH], 2009, p. 4), and are respectful of the health beliefs and practices, values, culture and linguistic needs of the individual, populations and communities (DoH, 2009, p. 12).

Culturally competent nursing requires practitioners to provide individualised care and consider their own values and beliefs impact on care provision. Critical reflection can assist nurses to work in the swampy ground of linguistic and cultural diversity. Reflection involves learning from experience: not simply thinking back over an event, but developing a conscious and systematic practice of thinking about experience in order to learn and change future behaviour. Critical reflection involves challenging the nurse’s understanding of themselves, their attitudes and behaviours in order to bring their views of practice and the world closer to the complex reality of care. This kind of process facilitates clinical reasoning, which is the thinking and decision-making toward undertaking the best-judged action, enhancing client care and improve practitioner capability and resilience.

Didactic approaches impart knowledge and provide students with declarative knowledge but don’t always provide the opportunity to practice communication techniques or to explore in depth the attitudes and behaviours that influence their own knowledge. Drama and theatre are increasingly being used to create dynamic simulated learning environments where students can try out different communication techniques in a safe setting where there are multiple ways of communicating. A problem based learning focus allows students to reflect on their own experiences and to arrive at their own solutions, promoting deep learning as students use their own experiences and knowledge to problem solve.

In 2015 I developed and trialed a unit for students at all three Monash School of Nursing and Midwifery campuses in their third year. The aim of the unit was to provide students with resources to understand their own culture, the culture of healthcare and the historical and social issues that contribute to differential health outcomes for particular groups in order to discern how to contribute to providing culturally safe care for all Australians. The unit examined how social determinants of health such as class, gender, race, sexual orientation, gender identity; education, economic status and culture affect health and illness. Students were invited to consider how politics, economics, the social-cultural environment and other contextual factors impacted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) communities. Students were asked to consider how policy, the planning, organisation and delivery of health and healthcare shaped health care delivery.

The unit was primarily delivered online but a special workshop was offered using Forum theatre developed by Augusto Boal in partnership with two experienced practitioners Azja Kulpińska and Tania Cañas. Forum theatre is focused on promoting dialogue between actors and audience members, it promotes transformation for social justice in the broader world and differs from traditional theatre which involves monologue. Simulated practices like Forum theatre allow students to address topics from practice within an educational setting, where they can safely develop self-awareness and knowledge to make sense of the difficult personal and professional issues encountered in complex health care environments. This is particularly important when it comes to inter-cultural issues and power relations. Such experiential techniques can help students to gain emotional competence, which in turn assists them to communicate effectively in a range of situations.

Students were invited to identify a professional situation relating to culture and health that was challenging and asked to critically reflect on the event/incident focusing on the concerns they encountered in relation to the care of the person. Through the forum theatre process they were asked to consider alternative understandings of the incident, and critically evaluate the implications of these understandings for how more effective nursing care could have been provided. Through the workshop it was hoped that students could then review the experience in depth and undertake a process of critical reflection in a written assessment by reconstructing the experience beyond the personal. They were encouraged to examine the historical and social factors that structure a situation and to start to theorise the causes and consequences of their actions. They were encouraged to use references such as research, policy documents or theory to support their analysis and identify an overarching issue, or key aspect of the experience that affected it profoundly. Concluding with the key learnings through the reflective process, the main factors affecting the situation, and how the incident/event could have been more culturally safe/competent. Students were asked to develop an action plan to map alternative approaches should this or a similar situation arise in the future.

Forum theatre has been used in nursing and health education to facilitate deeper and more critical reflective thinking, stimulate discussion and exploratory debate among student groups. It is used to facilitate high quality communication skills, critical reflective practice, emotional intelligence and empathy and appeals to a range of learning styles. Being able to engage in interactive workshops allows students to engage in complex issues increasing self-awareness using techniques include physical exercises and improvisations.

My grateful thanks to two Forum Theatre practitioners who led this work with me:

Azja Kulpińska is a community cultural development worker, educator and Theatre of the Oppressed practitioner and has delivered workshops both in Australia and internationally. She has been a supporter of RISE: Refugees, Survivors and Ex-Detainees and for the last 3 years has been co-facilitating a Forum Theatre project – a collaboration between RISE and Melbourne Polytechnic that explores challenging narratives around migration, settlement and systems of oppression. She is also a youth worker facilitating a support group for young queer people in rural areas.

Tania Cañas is a Melbourne-based arts professional with experience in performance, facilitation, cultural development and research. Tania is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Cultural Partnerships, VCA. She also sits on the International PTO Academic Journal.

She has presented at conferences both nationally and internationally, as well as facilitated Theatre of the Oppressed workshops at universities, within prisons and youth groups-in in Australian, Northern Ireland, The Solomon Islands, The United States and most recently South Africa. For the last 2.5 years has been working with RISE and Melbourne Polytechnic to develop a Forum Theatre program with students who are recent migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

References

- Australian Government. (2011). The People of Australia: Australia’s Multicultural Policy, Retrieved from https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/12_2013/people-of-australia-multicultural-policy-booklet.pdf

- Boud, D., Keogh, R. and Walker, D. 1985. Reflection: Turning experience into learning. London: Kogan Page.

- Gibbs, G. 1988. Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Oxford Further Education Unit.

- Johns, C. 1998b. Illuminating the transformative potential of guided reflection. In Transforming Nursing Through Reflective Practice (eds). C. Johns and D. Freshwater. Oxford: Blackwell Science. 78-90.

- Johnstone, MJ. & Kanitsaki, O. (2008). The politics of resistance to workplace cultural diversity education for health service providers: an Australian study. Race Ethnicity and Education 11(2) 133-134

- McClimens, A., & Scott, R. (2007). Lights, camera, education! The potentials of forum theatre in a learning disability nursing program. Nurse Education Today, 27(3), 203-9. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2006.04.009

- Middlewick, Y., Kettle, T. J., & Wilson, J. J. (2012). Curtains up! Using forum theatre to rehearse the art of communication in healthcare education. Nurse Education in Practice, 12(3), 139-42. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2011.10.010

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (2006). National competency standards for the registered nurse, viewed 16 February 2014: www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au.

- Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (2008). Code of professional conduct for nurses in Australia, Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia, Canberra.

- Schön, D.A. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- Street, A. 1990. Nursing Practice: High Hard Ground, Messy Swamps, and the Pathways in Between. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

- Turner, L. (2005). From the local to the global: bioethics and the concept of culture. Journal of Medicine and Philosopy. 30:305-320 DOI: 10.1080/03605310590960193

- Victorian Department of Health. (2009). Cultural responsiveness framework Guidelines for Victorian health services, Retrieved from http://www.health.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/381068/cultural_responsiveness.pdf

- Wasylko, Y., & Stickley, T. (2003). Theatre and pedagogy: Using drama in mental health nurse education. Nurse Education Today, 23(6), 443-448. doi:10.1016/s0260-6917(03)00046-7

- Also see DeSouza, R (2015). Communication central to Nursing Practice. Transforming the Nations Healthcare 2015, Australia’s Healthcare News.

Cite as: DeSouza, R. (2016, June 1st). Keynote address-Providing Culturally Safe Maternal and Child Healthcare, Multicultural Health Research to Practice Forum: Early Interventions in Maternal and Child Health, Program, Organised by the Multicultural Health Service, South Eastern Sydney, Local Health District, Australia. Retrieved fromhttp://ruthdesouza.dreamhosters.com/2016/06/11/cultural-safety-in-maternity/

Image from the film, the Namesake

A paragraph haunts me in The Namesake, Jhumpa Lahiri’s fictional account of the Indian immigrant experience. Ashoke and Ashima Ganguli migrate from Calcutta to Cambridge, Massachusetts after their arranged wedding. While pregnant, Ashima reflects:

Nothing feels normal. it’s not so much the pain which she knows she will survive. It’s the consequence: motherhood in a foreign land. For it was one thing to be pregnant to suffer the queasy mornings in bed, the sleepless nights, the dull throbbing in her back, the countless visits to the bathroom. Throughout the experience, in spite of her growing discomfort, she’s been astonished by her body’s ability to make life, exactly as her and grandmother and all her great grandmothers had done. That it was happening so far from home, unmonitored and unobserved by those she loved, had made it more miraculous still. But she is terrified to raise a child in a country where she is related to no one, where she knows so little, where life seems so tentative and spare. The Namesake, Jhumpa Lahiri

Ashima’s account beautifully captures the universality of the physical, embodied changes of maternity, the swelling, the nausea and other changes. But what Lahiri poignantly conveys is the singular emotional and cultural upheaval of these changes, the losses they give rise to. The absence of loving, knowledgeable, nurturing witnesses, the absence of a soft place to fall.

Arrival of baby girl in Prato, Tuscany. Credit DeSouza (2006).

In 1994 I worked on a post-natal ward where I was struck by the limits of universality and how treating everybody the same was problematic. For example, ostensibly beneficial practices like the routine administration of an icepack for soothing the perineum postnatally, or the imperative to mobilise quickly or to “room in” have potentially damaging effects on women whose knowledge frameworks differed from the dominant Pakeha culture of healthcare. These practices combined with a system designed for an imagined white middle class user, where professionals had knowledge deficits and monocultural and assimilatory attitudes, led to unsafe practices such as using family members and children as interpreters (my horror when a boy child was asked to ask his mother about the amount of lochia on her pad). The sanctity of birth, requiring the special, nurturing treatment of new mothers and a welcome from a community was superseded by the factory culture of maximum efficiency. Not all mothers were created equal, not young mothers, not older mothers, not single mothers, not substance using mothers, not indigenous mothers, not culturally different mothers. The sense that I was a cog in a big machine that was inattentive to the needs of “other” mothers led me to critique the effectiveness of cultural safety in the curriculum. How was it possible that a powerful indigenous pedagogical tool for addressing health inequity was not evident in clinical practice?

Photo of me as a staff nurse back in the day.

Leaving the post-natal ward, I took up a role helping to develop a new maternal mental health service in Auckland. There too I began to question the limitations of our model of care which privileged talking therapies rather than providing practical help and support. I was also staggered at the time at the raced and classed profile of our clients who were predominantly white middle class career women. Interestingly, the longer I was involved in the service the greater the number of ethnic women accessed the service. For my Master’s thesis, I interviewed Goan women about their maternity experiences in New Zealand, where the importance of social support and rituals in the perinatal period was noted by participants.

As much as it was important to register and legitimate cultural difference, I was also aware of the importance of not falling into the cultural awareness chasm. As Gregory Philips notes in his stunning PhD, it was assumed that through teaching about other cultures, needs would be better understood as “complex, equal and valid” (Philips, 2015). However, it didn’t challenge privilege, class and power. As Joan Scott points out:

There is nothing wrong, on the face of it, with teaching individuals about how to behave decently in relation to others and about how to empathize with each other’s pain. The problem is that difficult analyses of how history and social standing, privilege, and subordination are involved in personal behavior entirely drop out (Scott, 1992, p.9).

The problem with culturalism is that the notion of “learning about” groups of people with a common ethnicity assumes that groups of people are homogenous, unchanging and can be known. Their cultural differences are then viewed as the problem, juxtaposed against an implicit dominant white middle class cultural norm. This became evident in my PhD analysis of interviews with Korean mothers who’d birthed in New Zealand. In Australia and the US, cultural competence has superseded cultural awareness as a mechanism for correcting the limitations of universalism, by drawing attention to organisational and systemic mechanisms that can be measured but as a strategy for individual and interpersonal action, several authors draw attention to competence as being part of the “problem”:

The concept of multicultural competence is flawed… I question the notion that one could become “competent” at the culture of another. I would instead propose a model in which maintaining an awareness of one’s lack of competence is the goal rather than the establishment of competence. With “lack of competence” as the focus, a different view of practicing across cultures emerges. The client is the “expert” and the clinician is in a position of seeking knowledge and trying to understand what life is like for the client. There is no thought of competence—instead one thinks of gaining understanding (always partial) of a phenomenon that is evolving and changing (Dean, 2001, p.624).

In Wellness for all: the possibilities of cultural safety and cultural competence in New Zealand, I advocated for a combination of cultural competence and cultural safety. Cultural safety was developed by Indigenous nurses in Aotearoa New Zealand as a mechanism for considering and equalizing power relationships between client and practitioner. It is an ethical framework for practice derived from postcolonial and critical theory. Cultural safety proposes that practitioners reflect on how their status as culture bearers impacts on care, with care being deemed culturally safe by the consumer or recipient of care. In my PhD I wrote about the inadequacy of the liberal foundations of nursing and midwifery discourses for meeting the health needs of diverse maternal groups. My thesis advocated for the extension of the theory and practice of cultural safety to critique nursing’s Anglo-European knowledge base in order to extend the discipline’s intellectual and political mandate with the aim of providing effective support to diverse groups of mothers. In Australia, cultural responsiveness, cultural security and cultural respect are also used, you can read more about this on my post on Minding the Gap.

So let’s look at culturally safe maternity care. My experience as a clinician and researcher reveal a gap between how birth is viewed. In contemporary settler nations like New Zealand, midwifery discourses position birth as natural and the maternal subject as physically capable of caring for her baby from the moment it is born, requiring minimal intervention and protection. The maternal body is represented as strong and capable for taking on the tasks of motherhood. In contrast, many cultures view birth as a process that makes the body vulnerable, requiring careful surveillance and monitoring and a period of rest and nurturing before the new mother can take on new or additional responsibilities. The maternal body is seen as a body at risk (Mahjouri, 2008), and vulnerable requiring special care through rituals and support. Therefore, practices based on a dominant discourse of birth as a normal physiological event and neoliberal discourses of productive subjectivity create a gap between what migrant women expect in the care they expect from maternal services. These practices also constitute modes of governing which are intended to be empowering and normalizing, but are experienced as disempowering because they don’t take into account other views of birth. Consequently there is no recognition on the part of maternity services that for a short time, there is a temporary role change, where the new mother transitions into a caregiver by being cared for. This social transition where the mother is mothered is sanctioned in order to safeguard the new mother, a demonstration to value and protect both future capacity for mothering and long term well being, in contrast with dominant discourses of responsibilisation and intensive motherhood. Thus, instead of a few days of celebration or a baby shower, extended post-partum practices are enacted which can include the following (Note that these will vary depending on in group differences, urbanisation, working mothers, migration):

- Organised support- where family members (eg mother, mother-in-law, and other female relatives) care for the new mother and infant. Other women may also be involved eg birth attendants.

- Rest period and restricted practices- where women have a prescribed rest periods of between 21 days and five weeks, sometimes called “Doing the month”. Activities including sexual activity, physical and intellectual work are reduced.

- Diet- Special foods are prepared that promote healing/restore health or have a rebalancing function for example because the postpartum period is seen as a time when the body is cold, hot food (protein rich) chicken soup, ginger and seaweed, milk, ghee, nuts, jaggery might be consumed. Special soups and tonics with a cleansing or activating function are consumed eg to help the body expel lochia, to increase breastmilk. These foods might be consumed at different stages of the perinatal period and some food might be prohibited while breastfeeding.

- Hygiene and warmth- particular practices might be adhered to including purification/bathing practices eg warm baths, immersion. Others might include not washing hair.

- Infant care and breastfeeding- Diverse beliefs about colostrum, other members of family may take more responsibility while mother recovers and has a temporarily peripheral role. Breastfeeding instigation and duration may differ.

- Other practices include: binding, infant massage, maternal massage, care of the placenta.

If women are confronted with an unfamiliar health system with little support and understanding, they can experience stress, insecurity, loneliness, isolation, powerlessness, hopelessness. This combined with communication gaps and isolation, poor information provision, different norms, feeling misunderstood and feeling stigmatized. What could be a special time is perceived as a lack of care. Fortunately in Australia there are some excellent resources, for example this research based chapter on Cultural dimensions of pregnancy, birth and post-natal care produced by Victoria Team, Katie Vasey and Lenore Manderson, proposes useful questions for perinatal assessment which I have summarised below:

- Are you comfortable with both male and female health care providers?

- Are there any cultural practices that we need to be aware of in caring for you during your pregnancy, giving birth and postnatal period? – For example, requirements with the placenta, female circumcision or infant feeding method.

- In your culture, do fathers usually attend births? Does your partner want to attend the birth of his child? If not, is there another close family member you would like to be present? Would you like us to speak to them about your care?

- Are there any foods that are appropriate or inappropriate for you according to your religion or customs during pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period?

- Are there any beliefs or customs prohibiting physical activity during pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period? Do you plan to observe these? – For example, a confinement period.

- What is the culturally acceptable way for you to express pain during childbirth? – For example, screaming or trying to keep silent.

- Are there any precautions with infant care?

- How many visitors do you expect while you are in the hospital?

- Do you have anyone in your family or community who can help you in practical ways when you get home?

Negotiating between cultural practices, values and norms, religious beliefs and views, beliefs about perinatal care is a starting point. It is also important to consider language proficiency, health literacy, quality of written materials, and level of acculturation. For further information on health literacy see the Centre for Culture, Ethnicity & Health (CEH) resources including: What is health literacy?, Social determinants of health and health literacy. Using professional interpreters improves communication, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction and quality of care, and reduces medical testing, errors, costs and risk of hospitalisation. Lack of appropriate interpreter service use is associated with adverse health outcomes. Centre for Culture,Ethnicity & Health (CEH) has excellent resources in this regard: Interpreters: an introduction, Assessing the need for an interpreter, Booking and briefing an interpreter, Communicating via an interpreter, Debriefing with an interpreter, Developing a comprehensive language services response, Language services guide Managing bilingual staff, Planning for translation, Recruiting bilingual staff.

Assessment should also consider:

- Genetics and pregnancy: women’s age, parity, planning and acceptance of pregnancy, pregnancy related health behaviour and perceived health during pregnancy.

- Migration: women’s knowledge of/familiarity with the prenatal care services/system, experiences and expectations with prenatal care use in their country of origin, pregnancy status on arrival in the new industrialized western country.

- Culture: women’s cultural practices, values and norms, acculturation, religious beliefs and views, language proficiency, beliefs about pregnancy and prenatal care.

- Position in the host country: women’s education level, women’s pregnancy-related knowledge, household arrangement, financial resources and income.

- Social network: size and degree of contact with social network, information and support from social network.

- Accessibility: transport, opening hours, booking appointments, direct and indirect discrimination by the prenatal care providers.

- Expertise: prenatal care tailored to patients’ needs and preferences.

- Treatment and communication: communication from prenatal care providers to women, personal treatment of women by prenatal care providers, availability of health promotion/information material, use of alternative means of communication.

- Professionally defined need: referral by general practitioners and other healthcare providers to prenatal care providers

A review by Small, Roth et al., (2014) found that what immigrant and non-immigrant women want from maternity care is similar: safe, high quality, attentive and individualised care, with adequate information and support. Generally immigrant women were less positive about care than non-immigrant women, in part due to communication issues, lack of familiarity with care systems, perceptions of discriminatory care which was not kind or respectful. The challenge for health systems is to address the barriers immigrant women face by improving communication, increasing women’s understanding of care provision and reducing discrimination. Clinical skills including—introspection, self-awareness, respectful questioning, attentive listening, curiosity, interest, and caring.

Also:

- Facilitating trust, control

- Delivering quality, safe care, communicating, being caring, providing choices

- Facilitating access to interpreters and choice of gender of care provider,

- Considering cultural practices, preferences and needs/different expectations for care

- Engendering positive interactions, being empathetic, kind, caring and supportive.

- Taking concerns seriously

- Preserving dignity and privacy

- Seeing a person both as an individual, a family member and a community member

- Developing composure managing verbal and non-verbal expressions of disgust and surprise

- Paradoxical combination of two ideas— being “informed” and “not knowing” simultaneously.

In that sense, our knowledge is always partial and we are always operating from a position of incompletion or lack of competence. Our goal is not so much to achieve competence but to participate in the ongoing processes of seeking understanding and building relationships. This understanding needs to be directed toward ourselves and not just our clients. As we question ourselves we gradually wear away our own resistance and bias. It is not that we need to agree with our clients’ practices and beliefs; we need to understand them and under-stand the contexts and history in which they develop (Dean, 2001, p.628).

Conclusion

In this presentation I have invited you to examine your own values and beliefs about the perinatal period and how they might impact on the care you might provide. I have asked you to consider both the similarities and differences between how women from culturally diverse communities experience maternity and those from the dominant culture. Together, we have scrutinised a range of strategies for enhancing trust, engagement and perinatal outcomes for all women. Drawing on my own clinical practice and research, I have asked you to consider an alternative conceptualisation of the maternal body when caring for some women, that is the maternal body as vulnerable, which requires a period of rest and nurturing. This framing requires a temporary role change for the new mother to transition into being a caregiver, by being cared for, so that her future capacity for mothering and long term well being are enhanced. I have asked you to reflect on how supposedly empowering practices can be experienced as disempowering because they don’t take into account this view of birth. In the context of differing conceptualisations of birth and the maternal body I have drawn special attention to: negotiating between health beliefs; having cultural humility; considering ways in which your own knowledge is always partial; and recommended a range of resources that can be utilised to ensure positive outcomes for women and their families. As health services in Australia grapple with changing societal demographics including cultural diversity, changing consumer demands and expectations; resource constraints; the limitations in traditional health care delivery; greater emphasis on transparency, accountability, evidence- based practice (EBP) and clinical governance (Davidson et al., 2006), questions of how to provide effective universal health care can be enhanced by considering how differing views can be incorporated as they hold potential benefits for all.

Selected references

- Boerleider, A. W., Wiegers, T. A., Manniën, J., Francke, A. L., & Devillé, W. L. (2013). Factors affecting the use of prenatal care by non-western women in industrialized western countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 8.

- Dennis, C. L., Fung, K., Grigoriadis, S., Robinson, G. E., Romans, S., & Ross, L. (2007). Traditional postpartum practices and rituals: A qualitative systematic review. Women’s Health (London, England), 3(4), 487-502. doi:10.2217/17455057.3.4.487.

- Mander, S., & Miller, Y. D. (2016). Perceived safety, quality and cultural competency of maternity care for culturally and linguistically diverse women in queensland. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 3(1), 83-98. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0118.

- Small, R., Roth, C., Raval, M., Shafiei, T., Korfker, D., Heaman, M. Gagnon, A. (2014). Immigrant and non-immigrant womens experiences of maternity care: A systematic and comparative review of studies in five countries. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1).

Additional web resources

- The Victorian Refugee Health Network has maternity resources.

- Opportunities to improve maternal health literacy through antenatal education: an exploratory study, article by Susan Renkert and Don Nutbeam

On 15 February 2016, I spoke on 612 ABC Brisbane Afternoons with Kelly Higgins-Devine about cultural appropriation and privilege. Our discussion was followed by discussion with guests: Andie Fox – a feminist and writer; Carol Vale a Dunghutti woman; and Indigenous artist, Tony Albert. I’ve used the questions asked during the interview as a base for this blog with thanks to Amanda Dell (producer).

Why has it taken so long for the debate to escape academia to be something we see in the opinion pages of publications now?

Social media and online activism have catapulted questions about identities and politics into our screen lives. Where television allowed us to switch the channel, or the topic skilfully changed at awkward moments in work or family conversations, our devices hold us captive. Simply scrolling through our social media feeds can encourage, enrage or mobilise us into fury or despair. Whether we like it or not, as users of social media we are being interpolated into the complex terrain of identity politics. Merely sharing a link on your social media feed locates you and your politics, in ways that you might never reveal in real time social conversations. ‘Sharing’ can have wide ranging consequences, a casual tweet before a flight resulted in Justine Sacco moving from witty interlocutor to pariah in a matter of hours. The merging of ‘private’ and public lives never being more evident.

How long has the term privilege been around?

The concept of privilege originally developed in relation to analyses of race and gender but has expanded to include social class, ability level, sexuality and other aspects of identity. Interestingly, Jon Greenberg points out that although people of color have fought racism since its inception, the best known White Privilege educators are white (Peggy McIntosh, Tim Wise and Robin DiAngelo). McIntosh’s 1988 paper White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences through Work in Women’s Studies extended a feminist analysis of patriarchal oppression of women to that of people of color in the United States. This was later shortened into the essay White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (pdf), which has been used extensively in a a range of settings because of it’s helpful list format .

Many people have really strong reactions to these concepts – why is that?

Robin DiAngelo, professor of multicultural education and author of What Does it Mean to Be White? Developing White Racial Literacy developed the term ‘white fragility’ to identify:

a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include outward display of emotions such as anger, fear and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence and leaving the stress-inducing situation

DiAngelo suggests that for white people, racism or oppression are viewed as something that bad or immoral people do. The racist is the person who is verbally abusive toward people of color on public transport, or a former racist state like apartheid South Africa. If you see yourself as a ‘good’ person then it is painful to be ‘called out’, and see yourself as a bad person. Iris Marion Young’s work useful. She conceptualises oppression in the Foucauldian sense as:

the disadvantage and injustice some people suffer not because of a tyrannical power coerces them but because of the everyday practices of a well-intentioned liberal society…

Young points out the actions of many people going about their daily lives contribute to the maintenance and reproduction of oppression, even as few would view themselves as agents of oppression. We cannot avoid oppression, as it is structural and woven throughout the system, rather than reflecting a few people’s choices or policies. Its causes are embedded in the unquestioned norms, habits, symbols and assumptions underlying institutional rules and the collective consequences of following those rules (Young, 1990). Seeing oppression as the practices of a well intentioned liberal society removes the focus from individual acts that might repress the actions of others to acknowledging that “powerful norms and hierarchies of both privilege and injustice are built into our everyday practices” (Henderson & Waterstone, 2008, p.52). These hierarchies call for structural rather than individual remedies.

We probably need to start with privilege – what does that term mean?

McIntosh identified how she had obtained unearned privileges in society just by being White and defined white privilege as:

an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I am meant to remain oblivious (p. 1).

Her essay prompted understanding of how one’s success is largely attributable to one’s arbitrarily assigned social location in society, rather than the outcome of individual effort.

“I got myself where I am today. Honestly, it’s not that hard. I think some people are just afraid of a little hard work and standing on their own two feet, on a seashell, on a dolphin, on a nymph-queen that are all holding them up.”

From: The Birth of Venus: Pulling Yourself Out Of The Sea By Your Own Bootstraps by Mallory Ortberg

McIntosh suggested that white people benefit from historical and contemporary forms of racism (the inequitable distribution and exercise of power among ethnic groups) and that these discriminate or disadvantage people of color.

How does privilege relate to racism, sexism? Are they the same thing?

It’s useful to view the ‘isms’ in the context of institutional power, a point illustrated by Sian Ferguson:

In a patriarchal society, women do not have institutional power (at least, not based on their gender). In a white supremacist society, people of color don’t have race-based institutional power.

Australian race scholars Paradies and Williams (2008) note that:

The phenomenon of oppression is also intrinsically linked to that of privilege. In addition to disadvantaging minority racial groups in society, racism also results in groups (such as Whites) being privileged and accruing social power. (6)

Consequently, health and social disparities evident in white settler societies such as New Zealand and Australia (also this post about Closing the gap) are individualised or culturalised rather than contextualised historically or socio-economically. Without context white people are socialized to remain oblivious to their unearned advantages and view them as earned through merit. Increasingly the term privilege is being used outside of social justice settings to the arts. In a critique of the Hottest 100 list in Australia Erin Riley points out that the dominance of straight, white male voices which crowds out women, Indigenous Australians, immigrants and people of diverse sexual and gender identities. These groups are marginalised and the centrality of white men maintained, reducing the opportunity for empathy towards people with other experiences.

Do we all have some sort of privilege?

Yes, depending on the context. The concept of intersectionality by Kimberlé Crenshaw is useful, it suggests that people can be privileged in some ways and not others. For example as a migrant and a woman of color I experience certain disadvantages but as a middle class cis-gendered, able-bodied woman with a PhD and without an accent (only a Kiwi one which is indulged) I experience other advantages that ease my passage through the world You can read more in the essay Explaining White Privilege to a Broke White Person.

How does an awareness of privilege change the way a society works?

Dogs and Lizards: A Parable of Privilege by Sindelókë is a helpful way of trying to understand how easy it is not to see your own privilege and be blind to others’ disadvantages. You might have also seen or heard the phrase ‘check your privilege’ which is a way of asking someone to think about their own privilege and how they might monitor it in a social setting. Exposing color blindness and challenging the assumption of race-neutrality is one mechanism for addressing the issue of privilege and its obverse oppression. Increasingly in health and social care, emphasis is being placed on critiquing how our own positions contribute to inequality (see my chapter on cultural safety), and developing ethical and moral commitments to addressing racism so that equality and justice can be made possible. As Christine Emba notes “There’s no way to level the playing field unless we first can all see how uneven it is.” One of the ways this can be done is through experiencing exercises like the Privilege Walk which you can watch on video. Jenn Sutherland-Miller in Medium reflects on her experience of it and proposes that:

Instead of privilege being the thing that gives me a leg up, it becomes the thing I use to give others a leg up. Privilege becomes a way create equality and inclusion, to right old wrongs, to demand justice on a daily basis and to create the dialogue that will grow our society forward.

Is privilege something we can change?

If we move beyond guilt and paralysis we can use our privilege to build solidarity and challenge oppression. Audra Williams points out that a genuine display of solidarity can require making a personal sacrifice. Citing the example of Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, where in challenging the director of a commercial about the lack of women with speaking roles, he ends up not being in the commercial at all when it is re-written with speaking roles for women. Ultimately privilege does not gets undone through “confession” but through collective work to dismantle oppressive systems as Andrea Smith writes.

Cultural appropriation is a different concept, but an understanding of privilege is important, what is cultural appropriation?

Cultural appropriation is when somebody adopts aspects of a culture that is not their own (Nadra Kareem Little). Usually it is a charge levelled at people from the dominant culture to signal power dynamic, where elements have been taken from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by the dominant group. Most critics of the concept are white (see white fragility). Kimberly Chabot Davis proposes that white co-optation or cultural consumption and commodification, can be cross-cultural encounters that can foster empathy and lead to working against privilege among white people. However, an Australian example of bringing diverse people together through appropriation backfired, when the term walkabout was used for a psychedelic dance party. Using a deeply significant word for initiation rites, for a dance party was seen as disrespectful. The bewildered organiser was accused via social media of cultural appropriation and changed the name to Lets Go Walkaround. So, I think that it is always important to ask permission and talk to people from that culture first rather than assuming it is okay to use.

What is the line between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation?

Maisha Z. Johnson cultural appreciation or exchange where mutual sharing is involved.

Can someone from a less privileged culture appropriate from the more privileged culture?

No, marginalized people often have to adopt elements of the dominant culture in order to survive conditions that make life more of a struggle if they don’t.

Does an object or symbol have to have some religious or special cultural significance to be appropriated?

Appropriation is harmful for a number of reasons including making things ‘cool’ for White people that would be denigrated in People of Color. For example Fatima Farha observes that when Hindu women in the United States wear the bindi, they are often made fun of, or seen as traditional or backward but when someone from the dominant culture wears such items they are called exotic and beautiful. The critique of appropriation extends from clothing to events Nadya Agrawal critiques The Color Run™ where you can:

run with your friends, come together as a community, get showered in colored powder and not have to deal with all that annoying culture that would come if you went to a Holi celebration. There are no prayers for spring or messages of rejuvenation before these runs. You won’t have to drink chai or try Indian food afterward. There is absolutely no way you’ll have to even think about the ancient traditions and culture this brand new craze is derived from. Come uncultured, leave uncultured, that’s the Color Run, promise.

The race ends with something called a “Color Festival” but does not acknowledge Holi. This white-washing (pun intended) eradicates everything Indian from the run including Holi, Krishna and spring. In essence as Ijeoma Oluo points out cultural appropriation is a symptom, not the cause, of an oppressive and exploitative world order which involves stealing the work of those less privileged. Really valuing people involves valuing their culture and taking the time to acknowledge its historical and social context. Valuing isn’t just appreciation but also considering whether the appropriation of intellectual property results in economic benefits for the people who created it. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar suggests that it is often one way:

One very legitimate point is economic. In general, when blacks create something that is later adopted by white culture, white people tend to make a lot more money from it… It feels an awful lot like slavery to have others profit from your efforts.

Loving burritos doesn’t make someone less racist against Latinos. Lusting after Bo Derek in 10 doesn’t make anyone appreciate black culture more… Appreciating an individual item from a culture doesn’t translate into accepting the whole people. While high-priced cornrows on a white celebrity on the red carper at the Oscars is chic, those same cornrows on the little black girl in Watts, Los Angeles, are a symbol of her ghetto lifestyle. A white person looking black gets a fashion spread in a glossy magazine; a black person wearing the same thing gets pulled over by the police. One can understand the frustration.

The appropriative process is also selective, as Greg Tate observes in Everything but the burden, where African American cultural properties including music, food, fashion, hairstyles, dances are sold as American to the rest of the world but with the black presence erased from it. The only thing not stolen is the burden of the denial of human rights and economic opportunity. Appropriation can be ambivalent, as seen in the desire to simultaneously possess and erase black culture. However, in the case of the appropriation of the indigenous in the United States, Andrea Smith declares (somewhat ironically), that the desire to be “Indian” often precludes struggles against genocide, or demands for treaty rights. It does not require being accountable to Indian communities, who might demand an end to the appropriation of spiritual practices.

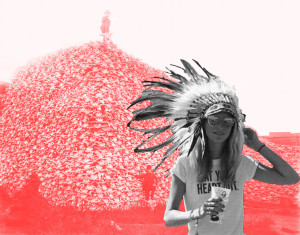

Go West – Black: Random Coachella attendee, 2014. Red: Bison skull pile, South Dakota, 1870’s by Roger Peet.

Some people believe the cuisines of other cultures have been appropriated – is this an extreme example, or is it something we should consider?

The world of food can be such a potent site of transformation for social justice. I am a committed foodie (“somebody with a strong interest in learning about and eating good food who is not directly employed in the food industry” (Johnston and Baumann, 2010: 61). I am also interested in the politics of food. I live in Melbourne, where food culture has been made vibrant by the waves of migrants who have put pressure on public institutions, to expand and diversify their gastronomic offerings for a wider range of people. However, our consumption can naturalise and make invisible colonial and racialised relations. Thus the violent histories of invasion and starvation by the first white settlers, the convicts whose theft of food had them sent to Australia and absorbed into the cruel colonial project of poisoning, starving and rationing indigenous people remain hidden from view. So although we might love the food we might not care about the cooks at all as Rhoda Roberts Director of the Aboriginal Dreaming festival observed in Elspeth Probyn’s excellent book Carnal Appetites:

In Australia, food and culinary delights are always accepted before the differences and backgrounds of the origin of the aroma are.

Lee’s Ghee is an interesting example of appropriation, she developed an ‘artisanal’ ghee product, something that has been made for centuries in South Asia.

Lee Dares was taking the fashion world by storm working as a model in New York when she realized her real passion was elsewhere. So, she made the courageous decision to quit her glamorous job and take some time to explore what she really wanted to do with her life. Her revelation came after she spent some time learning to make clarified butter, or ghee, on a farm in Northern India. Inspired, she turned to Futurpreneur Canada to help her start her own business, Lee’s Ghee, producing unique and modern flavours of this traditional staple of Southeast Asian cuisine and Ayurvedic medicine.

The saying “We are what we eat” is about not only the nutrients we consume but also to beliefs about our morality. Similarly ‘we’ are also what we don’t eat, so our food practices mark us out as belonging or not belonging to a group.So, food has an exclusionary and inclusionary role with affective consequences that range from curiosity, delight to disgust. For the migrant for example, identity cannot be taken for granted, it must be worked at to be nurtured and maintained. It becomes an active, performative and processual project enacted through consumption. With with every taste, an imagined diasporic group identity is produced, maintained and reinforced. Food preparation represents continuity through the techniques and equipment that are used which affirm family life, and in sharing this food hospitality, love, generosity and appreciation can be expresssed. However, the food that is a salve for the dislocated, lonely, isolated migrant also sets her apart, making her stand out as visibly, gustatorily or olfactorily different. The resource for her well being also marks her as different and a risk. If her food is seen as smelly, distasteful, foreign, violent or abnormal, these characteristics can be transposed to her body and to those bodies that resemble her. Dares attempt to reproduce food that is made in many households and available for sale in many ‘ethnic’ shops and selling it as artisanal, led to accusations of ‘colombusing’ — a term used to describe when white people claim they have discovered or made something that has a long history in another culture. Also see the critique by Navneet Alang in Hazlitt:

The ethnic—the collective traditions and practices of the world’s majority—thus works as an undiscovered country, full of resources to be mined. Rather than sugar or coffee or oil, however, the ore of the ethnic is raw material for performance and self-definition: refine this rough, crude tradition, bottle it in pretty jars, and display both it and yourself as ideals of contemporary cosmopolitanism. But each act of cultural appropriation, in which some facet of a non-Western culture is columbused, accepted into the mainstream, and commodified, reasserts the white and Western as norm—the end of a timeline toward which the whole world is moving.

If this is the first time someone has heard these concepts, and they’re feeling confused, or a bit defensive, what can they do to understand more about it?

Here are some resources that might help, videos, illustrations, reading and more.

White privilege

- Toby Morris has created a beautiful illustration of Privilege.

- A hilarious look at white male privilege by Elliot Kalan.

- Video White privilege glasses from Chicago Theological Seminar.

- 11 Common Ways White Folks Avoid Taking Responsibility for Racism in the US by Robin DiAngelo.

- A great edited book on whiteness in Australia: Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism By Aileen Moreton-Robinson

- McSweeney’s have some hilarious writing on privilege including: a humorous product review of the invisible backpack of white privilege from by Joyce Miller; Don’t worry, I checked my privilege by Elliot Kalan; Some relatively recent College grads discuss their maids by Ellie Kemper and Privilege-checking preambles of varying degrees of singularity by George Morony.

- 4 Ways White People Can Process Their Emotions Without Bringing the White Tears by Jennifer Loubriel.

- The fairest — and funniest — way to split a restaurant bill by Emily Badger·

- See the excellent work on privilege by the Whariki Research Group, Massey University, New Zealand.

- Read about the reductive seduction of other people’s problems.

- Read more about whiteness, in an interview with Robin DiAngelo.

- Tim Wise has tons of resources.

- Check your privilege at the door.

- View the Unequal Opportunity Race. Screened as part of the Black History Month program at Glen Allen High School in Glen Allen, Virginia.

- This piece by Ali Owens about 4 problematic statements White people make about race — and what to say instead is useful: “I Don’t See Color.” “All Lives Matter.” “If racism is still a problem, how come we have a black president?” “Reverse racism is real.”

- The eight ways of being white by Gillian Schutte examines Barnor Hesses’ work (about whiteness studies from a radical black perspective) outlining the eight categories of white identity.

- An interesting read about privilege in sport using the example of Maria Sharapova and Serena Williams: The Benefit of the Doubt: A Case Study On White Privilege.

- Whiteness as Metaprivilege.

- The Subtle Linguistics of Polite White Supremacy.

- If you’d like to try the group exercise on privilege adapted from the Horatio Alger exercise by Ellen Bettman, you can read the questions here.

- Oscar Kightley’s terrific take down of the myth of Maori privilege.

- Brown eye asking about whether Maori seats in New Zealand is privileging Maori.

- A sobering read Death by gentrification: the killing that shamed San Francisco | Rebecca Solnit.

Cultural appropriation

- Aarti Olivia has a lovely piece on when it is appropriate to wear Indian cultural items.

- An exploration of Orientalism & Asian cultural appropriation as found in American music by Ube Empress.

- A much-needed primer on cultural appropriation by Katie J.M. Baker.

- More about food and cultural appropriation by Niya Bajaj.

- Check out this exploration of visual and auditory appropriation in US culture by Portland artist Roger Peet, featuring local residents.

- A critique of appropriation in fashion, Valentino’s African summer in Parallel magazine.

- I’ve written about cultural consumption in this piece on food and festivals, also about the white saviour complex and moving from being a bystander to an ally.

- A useful explanation on the meaning of a Native American headdress and why not to wear one.

- Brilliant piece by Texta Queen on cultural appropriation, white privilege and art on the fabulous Peril site.

This is a longer version of a review of Damien Riggs & Clare Bartholomaeus’ paper published in the Journal of Research in Nursing: Australian mental health nurses and transgender clients: Attitudes and knowledge. Cite as: De Souza, R. (2016). Review: Australian mental health nurses and transgender clients: Attitudes and knowledge. Journal of Research in Nursing, 0(0) 1–2. DOI: 10.1177/1744987115625008

I have never forgotten her face, her body, even though more than twenty years have passed. She was not much older than me and she desperately wanted to be a he. I had no idea how to respond to her depression and her recent self-harm attempt in the context of her desire to change gender. There was nothing in my nursing education that had prepared me for how I might be therapeutic and there was no one and nothing in the acute psychiatric inpatient unit that could resource me. I feel embarrassed now that I had no professional understanding and experience to guide me to help me provide effective mental health care to my client. I was an empathic kind listener, but I had been immersed in a biologically deterministic (one’s sex at birth determines ones’ gender) and binary view of gender despite my own diverse cultural background which I had been socialized to see as separate from my mainly white nursing education. I had not been educated to critically consider discourses of sex and gender, to provide competent safe care to someone who wanted to change her gender and express her gender differently from normative gender categories (Merryfeather & Bruce, 2014). My work has since led me to consider the ways in which “differences” are produced culturally, politically, and epistemologically specifically in terms of categories including “race”, ethnicity, nationality, class, and more recently sexuality and gender.

Four critiques of biomedicine as a dominant framework for understanding ‘problems with living’ have inspired transformation of the mental health system. Firstly, the emphasis on participation and inclusion through consumer-led and recovery-oriented practice has profoundly changed the role of consumers from passive recipients of care to being more informed and empowered decision-makers whose lay knowledge and personal experience of mental illness are a resource (McCann and Sharek, 2014). This reconceptualisation has been formalised in the ‘recovery’ model, which has critiqued the stigmatising judgements of medico-psychiatric discourse about deviance and their accompanying social exclusion and disadvantage (Masterson and Owen, 2006). The third has been the recognition of cultural diversity and a critique of the limits of universalism. Finally, gender activism has exposed fractures in the sex/gender system and has led to a greater awareness of diversity, with regard to gender and sexual orientation.

Of these critiques, gender activism has received the least attention in mental health nursing; which is a concern, given the negative effects of heteronormativity and cisgenderism. Mental health nurses must continue to challenge or trouble the dominant binary views of gender and the discourse of biological determinism, the notion that the sex that one is assigned at birth determines ones’ gender (Merryfeather and Bruce, 2014). There is growing evidence of negative attitudes, a lack of knowledge, and a lack of sensitivity toward people whom are expressing diverse genders and sexualities. This discrimination creates barriers to the patients’ health gain and creates disparity (Chapman et al., 2012; McCann and Sharek, 2014).

The reviewed article on the attitudes of mental health nurses towards transgender people is therefore timely, given the relative invisibility of issues of gender identity within nursing theory, practice and research. As Fish (2010) wrote previously in this journal, the culture, norms and values of social institutions can inhibit access to healthcare and reinforce disparities in health outcomes. Cisgenderism (the alignment of one’s assigned sex at birth and one’s gender identity and gender expression with societal expectations) suffuses every aspect of clinical access to and through services, from written materials including mission statements, forms, posters and pamphlets; the built environment such as gender-specific washrooms; and interactions with both health professionals and allied staff, all of which reinforce a message of exclusion of transgender people (Baker and Beagan, 2014; Rager Zuzelo, 2014). In turn, these exclusionary practices are shaped through a dearth of policies and procedures, and scant educational preparation at the undergraduate and graduate levels (Eliason et al., 2010; Fish, 2010).

Nurses have a professional responsibility to challenge structural constraints and social policies, rather than passively accepting them. This paper provided compelling evidence for how nursing as a discipline and mental health nursing as a unique speciality can critically reflect on discourses regarding sex and gender; and on how these influence practice and consequently, can develop safer, ethical, effective and high-quality care for people whom either change their sex or express their gender differently from the standard culturally determined gender categories (Merryfeather and Bruce, 2014). Furthermore, this paper challenges mental health nurses to challenge heterosexism and cisgenderism; to speak out about social determinants of health that contribute to health inequities and health disparities, such as transphobia; and to address discrimination against transgender people. These challenges must be embedded into processes at the organizational, regulatory and political level (DeSouza, 2015).

References

Baker K and Beagan B (2014) Making assumptions, making space: An anthropological critique of cultural competency and its relevance to queer patients. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 28(4): 578–598. doi:10.1111/maq.1212.

Chapman R, Watkins R, Zappia T, et al. (2012) Nursing and medical students’ attitude, knowledge and beliefs regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender parents seeking health care for their children. Journal of Clinical Nursing 21(7,8): 938–945. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03892.

De Souza R (2015) Navigating the ethics in cultural safety. In: Wepa D (ed.) Cultural safety. Port Melbourne, Australia: Cambridge University Press, pp. 111–124.

Eliason MJ, Dibble S and Dejoseph J (2010) Nursing’s silence on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues: The need for emancipatory efforts. Advances in Nursing Science 33(3): 206–218. doi:10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181e63e4.

McCann E and Sharek D (2014) Challenges to and opportunities for improving mental health services for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in Ireland: A narrative account. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 23(6): 525–533. doi:10.1111/inm.12081.

Masterson S and Owen S (2006) Mental health service user’s social and individual empowerment: Using theories of power to elucidate far-reaching strategies. Journal of Mental Health 15(1): 19–34. doi:10.1080/0963823050051271.

Merryfeather L and Bruce A (2014) The invisibility of gender diversity: Understanding transgender and transsexuality in nursing literature. Nursing forum 49(2): 110–123.

Rager Zuzelo P (2014) Improving nursing care for lesbian, bisexual and transgender women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 43(4): 520–530. doi:10.1111/1552-6909.1247.

December 18th marks the anniversary of the signing of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families by the United Nations in 1990. Lobbying from Filipino and other Asian migrant organisations in 1997, led to December18th being promoted as an International Day of Solidarity with Migrants. The day recognises the contributions of migrants to both the economies of their receiving and home countries, and promotes respect for their human rights. However, as of 2015, the Convention has only been signed by a quarter of UN member states.

2015 has seen the unprecedented displacement of people globally with tragic consequences. UNHCR’s annual Global Trends report shows a massive increase in the number of people forced to flee their homes. 59.5 million people were forcibly displaced at the end of 2014 compared to 51.2 million a year earlier and 37.5 million a decade ago.

Politicians and media have a pivotal role in agenda setting and shaping public opinion around migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. A 100-page report, Moving Stories, released for International Migrants Day reviews media coverage of migration across the European Union and 14 countries across the world. The report acknowledges the vulnerability of refugees and migrants and the propensity for them to be politically scapegoated for society’s ills and has five key recommendations, briefly (p.8):

- Ethical context: that the following five core principles of journalism are adhered to:

accuracy, independence, impartiality, humanity and accountability; - Newsroom practice: have diversity in the newsroom, journalists with specialist knowledge, provide detailed information on the background of migrants and refugees and the consequences of migration;

- Engage with communities: Refugee groups, activists and NGOs can be briefed

on how best to communicate with journalists; - Challenge hate speech.

- Demand access to information: When access to information is restricted, media and civil society groups should press the national and international governments to be more transparent.

Much remains to be done, but it is heartening to see Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s response to the arrival of thousands of Syrian refugees:

You are home…Welcome home…

Tonight they step off the plane as refugees, but they walk out of this terminal as permanent residents of Canada. With social insurance numbers. With health cards and with an opportunity to become full Canadians

Trudeau’s response sharply contrasts with that of the United States, where many politicians have responded to Islamophobic constituencies with restrictions or bans on receiving refugees. The welcome from Indigenous Canadians to newly arrived refugees has also been generous and inclusive, considering that refugees and migrants are implicated in the ongoing colonial practices of the state. These practices can maintain Indigenous disadvantage while economic, social and political advantage accrue to settlers. It is encouraging that Trudeau’s welcome coincided with an acknowledgement of the multiple harms Canada has imposed on Indigenous people since colonisation.

Alarmingly, the center-right Danish government’s bill currently before the Danish Parliament on asylum policy, allows for immigration authorities to seize jewellery and other valuables from refugees in order to recoup costs. The capacity to remove personal valuables from people seeking sanctuary is expected to be effective from February 2016 and has a chilling precedent in Europe, as Dylan Matthews notes in Vox:

Denmark was occupied by Nazi Germany for five years, from 1940 to 1945, during which time Germany confiscated assets from Jewish Danes, just as it did to Jews across Europe. Danish Jews saw less seized than most nations under Nazi occupation; the Danish government successfully prevented most confiscations until 1943, and Danes who survived the concentration camps generally returned to find their homes as they had left them, as their neighbors prevented Nazis from looting them too thoroughly. But Nazi confiscations still loom large in European historical memory more generally.

The UN, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) have advocated for the development of regional and longer term responses. Statements echoed by Ban Ki-moon which proposed better cooperation and responsibility sharing between countries and the upholding of the human rights of migrants regardless of their status (Australia take note). He proposes that we:

must expand safe channels for regular migration, including for family reunification, labour mobility at all skill levels, greater resettlement opportunities, and education opportunities for children and adults.

On International Migrants Day, let us commit to coherent, comprehensive and human-rights-based responses guided by international law and standards and a shared resolve to leave no one behind.

What does this all mean for Australia and New Zealand? I’ve written elsewhere about the contradiction between the consumptive celebrations of multiculturalism and the increasing brutality and punitiveness of policies in both countries; the concerns of Australia’s key professional nursing and midwifery bodies about the secrecy provisions in the Australian Border Force Act 2015 and the ways in which New Zealand is emulating a punitive and dehumanising Australian asylum seeker policy.

It is appropriate then in this season of goodwill and peace to write an updated Christmas wish list, but with a migration focus. As a child growing up in Nairobi, one of my pleasures around Christmas time was drawing up such a list. I was so captivated with this activity that I used to drag our Hindu landlord’s children into it. This was kind of unfair as I don’t think they received any of the gifts on their list. For those who aren’t in the know, a wish list is a list of goods or services that are wanted and then distributed to family and friends, so that they know what to purchase for the would-be recipient. The idea of a list is somewhat manipulative as it is designed around the desires of the recipient rather than the financial and emotional capacity of the giver. Now that I’ve grown up a little, I’ve eschewed the consumptive, labour exploitative, commercial and land-filling aspects of Christmas in favour of spending time with family, as George Monbiot notes in his essay The Gift of Death:

They seem amusing on the first day of Christmas, daft on the second, embarrassing on the third. By the twelfth they’re in landfill. For thirty seconds of dubious entertainment, or a hedonic stimulus that lasts no longer than a nicotine hit, we commission the use of materials whose impacts will ramify for generations.

So, this list focuses on International Day of Solidarity with Migrants. All I want for Christmas is that ‘we’:

- End the Australian Government policy of turning back people seeking asylum by boat ie “unauthorised maritime arrivals”.

- Stop punishing the courageous and legitimate right to seek asylum with the uniquely cruel policy of mandatory indefinite detention and offshore processing. Mandatory detention must end. It is highly distressing and has long-term consequences.

- Remove children and adolescents from mandatory detention. Children, make up half of all asylum seekers in the industrialized world. Australia, The United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy directly contradict The Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

- Engage in regional co-operation to effectively and efficiently process refugee claims and provide safe interim places. Ensure solutions that uphold people’s human rights and dignity, see this piece about the Calais “Jungle”.

- End the use of asylum-seeker, refugee and migrant bodies for political gain.

- Demand more ethical reporting by having news media: appoint specialist migration reporters; improve training of journalists on migration issues and problems of hate-speech; create better links with migrant and refugee groups; and employ journalists from ethnic minority communities, see Moving Stories.

- Follow the money. Is our money enabling corporate complicity in detention? Support divestment campaigns, see X Border Operational matters. Support pledges that challenge the outsourcing of misery for example No Business in Abuse (NBIA) who have partnered with GetUp.

- Support the many actions by Indigenous peoples to welcome refugees. Indigenous demands for sovereignty and migrant inclusion are both characterised as threats to social cohesion in settler-colonial societies.

- Challenge further racial injustice through social and economic exclusion and violence that often face people from migrantnd refugee backgrounds.

- Ask ourselves these questions:‘What are my borders?’ ‘Who do I/my community exile?’ ’How and where does my body act as a border?’ and ‘What kind of borders exist in my spaces?’ The questions are from a wonderful piece by Farzana Khan.

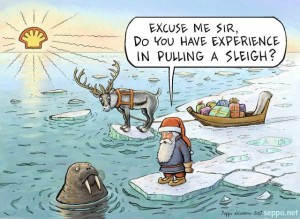

Seppo Leinonen, a cartoonist and illustrator from Finland

Speech given at the launch of a partnership between Monash University and Centre for Culture, Ethnicity and Health (CEH) April 29th 2015 and the celebration of CEH’s 21st birthday.

I would like to show my respect and acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land on which this launch takes place, the Wurundjeri-willam people of the Kulin Nation, their elders past and present. I’d also like to acknowledge our special guests: The Honorable Robin Scott – Minister for Multicultural Affairs/Minister for Finance, Phillip Vlahogiannis the Mayor of the City of Yarra, Chris Atlis the Deputy Chair of North Richmond Community Health (NRCH), Councillor Misha Coleman and Baraka Emmy, Youth Ambassador for Multicultural Health and Support Services. I’d also like to acknowledge: Professor Wendy Cross; CEO of the Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (CEH) Demos Krouskos; General Manager of CEH Michal Morris, representatives from the Department of Health and Human Services and other government departments, healthcare service partners, clients, NRCH and CEH staff and community members.

It’s an honour to take up this joint appointment between the Centre for Culture Ethnicity and Health (CEH) and Monash School of Nursing and Midwifery, there are some wonderful synergies which allow both organisations to jointly advance a shared goal of equity and quality in health care for our communities, and in particular for people from refugee and migrant background communities. As most of you know, Victoria is the most culturally diverse state in Australia, with almost a quarter of our population born overseas. Victorians come from over 230 countries, speak over 200 languages and follow more than 135 different faiths. This role is an acknowledgement of this diversity, and the need for health and social services that are equitable, culturally responsive and evidence based.

The gap this role addresses

Monash takes its name from Sir John Monash: an Australian, well known for being both a scholar and a man of action. He is quoted as having said “…equip yourself for life, not solely for your own benefit but for the benefit of the whole community.” I am excited about the ways in which this new role can both strengthen CEH’s leadership and expertise in culture and health; and strengthen Monash’s position as a provider of dynamic and collaborative research-led education. In thinking about the world of the university and the world of practice, the words of Abu Bakr resonate: “Without knowledge, action is useless and knowledge without action is futile.”

What we have in common

I believe this relationship combines knowledge and action which will benefit both organisations and their staff, but even more importantly the communities that we are all here to serve. Key to this partnership success is the generous and collaborative spirit with which the leadership of both organisations have come together and which bodes well for the future. What we have in common as organisations is:

- Firstly, a commitment to responsive clinical models of care that consider social determinants of health. In a world where health is increasingly industrialised and individualised, both Monash and CEH affirm the importance of communities in a healthy society

- Secondly, both organisations aim to develop a health and social workforce that can work effectively and safely with our communities. CEH and NRCH know how to work with communities, having expertise in advocacy and community-building roles advocacy and community-building roles to contribute to healthier social and physical environments. Monash know how to educate and inspire practitioners to link their practical knowledge to the centuries of research and scholarship that universities are custodians of around the world.

- Thirdly, the two organisations aim to keep clients and their families at the centre of care, to recognise that despite all our professional expertise it is the recipient of care who ultimately determines successful outcomes.

- Fourthly, the organisations seek a system of care that is both just and equitable – just as the university seeks truths that are universal while we research in the here and now, so too we need more than ever to maintain our ideal of a healthy society for all.

Dr Ruth De Souza, Professor Wendy Cross, Michal Morris, The Hon Robin Scott – Minister for Multicultural Affairs/Minister for Finance.

Benefits of the relationship

I forsee a number of benefits for both organisations from this role. CEH has a distinguished track record in supporting health and social practitioners to respond sensitively and effectively to the issues faced by people people from refugee and migrant backgrounds , and this will be of benefit to students and staff at Monash as we prepare a rapidly changing workforce for a rapidly changing workplace.

Monash has an international reputation for high quality and research and education, and CEH will use this expertise to advocate and campaign for change. CEH will be exposed to the university’s dynamic intellectual environment and its knowledge of global currents in cultural research and health research, strengthening its expertise in cultural competence and giving the organisation a platform to lead a much needed translational research agenda.