VALA Libraries, Technology and the Future invited my fabulous colleague from Melbourne University Fiona Tweedie and I to participate in a webinar discussion as part of Open Access Week. The webinar was hosted by VALA President, Katie Haden. VALA are an independent Australian based not-for-profit organisation that aim to promote the use and understanding of information technology within libraries and the broader information sector.

Is “Open” always “Equitable”?

The theme for Open Access Week for 2018 is ‘Designing equitable foundations for open knowledge.’ But open systems aren’t always set to a default of ‘inclusive’, and there are important questions that need to be raised around prioritisation of voices, addressing perpetual conscious and unconscious bias, and who is excluded from discussions and decisions surrounding information and data access. There are also issues of the sometimes-competing pressures to move toward both increased openness and greater privacy, the latter issue having much currency in the health domain (and more broadly) at present.

- If we default to inclusive, what does that look like?

- How do we address conscious and unconscious bias?

- How do we prioritise voices, identify who is included and/or excluded from discussions?

- How do we address the pressure to move toward both increased openness and greater privacy, particularly in the area of health data?

You can download the mp4 file of the webinar, or read a summary of what I had to say below.

Most of what I have learned about how to be a good nurse has come from the consumers I have worked with in my clinical practice. I think the people that live most closely to a phenomenon have a unique microscopic vantage point and that as a researcher and clinician, complementing this lived experience with a telescopic view allows us to see both the big picture and the lived experience. Similarly, my experience of innovations in health have been consumer driven: the initiation of text reminders in a health organisation I used to work for because newly arrived Sudanese women asked for it; health promotion activities that included fun and community building, because Pasifika people in South Auckland wanted something more communal. So I am interested in the emergence of data and technology as democratising enablers for groups that experience marginalisation. Consumers with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) who challenged the influential £5m publicly funded PACE trial which shaped research, treatment pathways and medical and public attitudes towards the illness are an example of how making data open and transparent can be transformative.

The PACE trial found that Cognitive Behavioural therapy (CBT) and Graded Exercise Therapy (GET) achieved 22 percent recovery rates (rather than just improvement rates) as opposed to only seven or eight percent in the control groups who did not engage in CBT and GET. The findings contradicted with the experiences of consumers, who suffered debilitating exhaustion after activities of daily living. A five year struggle by Australian Alem Matthees and supported by many scientists around the world who doubted the study’s conclusion resulted in Queen Mary University of London releasing the original data under the UK Freedom of information (FOI) Act at a cost of £250,000. When challenged about the distress that this had caused patients with ME/CFS the researchers claimed to be concerned about the ethics of sharing the data. However, Geraghty (2017) points out:

did PACE trial participants really ask for scientific data not to

be shared, or did participants simply ask that no personal identifiable information (PIIs) be disclosed?

Subsequent reanalysis showed recovery rates had been inflated and that the recovery rates in the CBT and GET groups were not significantly higher than in the group that received specialist medical care alone. One of the strategies for addressing the lack of transparency in science is to make data open (particularly if another £5m is unavailable to reproduce the study), sharing data, protocols, and findings in repositories that can be accessed and evaluated by other researchers and the public in order to enhance the integrity of research. Funding bodies are now increasingly making data-sharing a requirement of any research grant funding.

This story captures the value proposition of making health data open, it can: hold healthcare organizations/ providers accountable for treatment outcomes; help patients make informed choices from options available to them (shared decision making); improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of healthcare delivery; improve treatment outcomes by using open data to make the results of different treatments, healthcare organizations, and providers’ work more transparent; be used to educate patients and their families and make healthcare institutions more responsive; fuel new healthcare companies and initiatives, and to spur innovation in the broader economy (Verhulst et al, 2014).

The growing philosophy of open data which is about democratising data and enabling the sharing of datasets has been accompanied by other data related trends in health including: big data-large linked data from electronic patient records; streams of real-time geo-located health data collected by personal wearable devices etc; and new data sources from non-traditional sources eg social and environmental data (Kostkova, 2016). All of which can be managed through computation and algorithmic analysis. Arguments for open data in health include that because tax payers pay for its collection it should be available to them and that the value of data comes from being used by interpreting, analysing and linking it (Verhulst et al., 2014).

According to the open data handbook, open data refers to:

A piece of data or content is open if anyone is free to use, reuse, and redistribute it — subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and/or share-alike.

Usually it has three main features:

Availability and Access: the data must be available as a whole and at no more than a reasonable reproduction cost, preferably by downloading over the internet. The data must be available in a convenient and modifiable form.

Reuse and Redistribution: the data must be provided under terms that permit reuse and redistribution including the intermixing with other datasets.

Universal Participation: everyone must be able to use, reuse and redistribute – there should be no discrimination against fields of endeavour or against persons or groups.

Central to which is the idea of interoperability, whereby diverse systems and organizations can work together (inter-operate) or intermix different datasets.

Here are two useful examples of open data being used for the common good. The first concerns statins, which are widely prescribed and cost more than £400m out of a total drug budget of £12.7 billion pounds in England. Mastodon C (data scientists and engineers), The Open Data Institute (ODI) and Ben Goldacre analyzed how statins were prescribed across England and found widespread geographic variations. Some GPs were prescribing the patented statins which cost more than 20 times the cost of generic statins when generics worked just as well. The team suggested that changing prescription patterns could result in savings of more than 1 billion pounds per year. Another study showed how asthma hotspots could be tracked and used to help people with asthma problems to avoid places that would trigger their asthma. Participants were issued with a small cap that fit on a standard inhaler, when the inhaler was used, the cap recorded the time and location, using GPS circuitry. The data was captured over long periods of time and aggregated with anonymized data across multiple patients to times and places where breathing is difficult, that could help other patients improve their condition(Verhulst et al, 2014).

Linking and analysing data sets can occur across the spectrum of health care from clinical decision support, to clinical care, across the health system, to population health and health research. However, while the benefits are clear, there are significant issues at the individual and population level. In this tech utopia there’s an assumption of data literacy, that people who are given more information about their health will be able to act on this information in order to better their health. Secondly, data collected for seemingly beneficial purposes can impact on individuals and communities in unexpected ways, for example when data sets are combined and adapted for highly invasive research (Zook et al, 2017). Biases against groups that experience poor health outcomes can also be reproduced depending on what type of data is collected and with what purpose (Faife, 2018).

The concern with how data might be deployed and who it might serve is echoed by Virginia Eubanks Associate Professor of Political Science at the University at Albany, SUNY. Her book gives examples of how data have been misused in contexts including criminal justice, welfare and child services, exacerbating inequalities and causing harm. Frank Pasquale in a critique of big data and automated judgement has identified how corporations have compiled data and created portraits using decisions that are neither neutral or technical. He and others call for transparency, accountability and the protection of citizen’s rights by ensuring algorithmic judgements are fair, nondiscriminatory, and open to criticism. However, it is difficult for people from marginalised groups to challenge or interrogate systems or seek redress if harmed for example through statistical aggregation, so fostering dissent and collaboration by public authorities is necessary. Groups with the worst health outcomes have limited access to interventions or the determinants of health to begin with. So, it’s important to ensure that policy and regulation drive structural changes rather than embedding existing discrimination that exposes minority groups to increased surveillance and marginalisation (Redden, 2018).

The advent of Australia’s A$18.5 million national facial recognition system, the National Facial Biometric Matching Capability will allow federal and state governments access to access passport, visa, citizenship, and driver licence images to rapidly match pictures of people captured on CCTV “to identify suspects or victims of terrorist or other criminal activity, and help to protect Australians from identity crime“. The Capability is made up of two parts, the first comprises a Face Verification Service (FVS) which is already operational and allows for a one-to-one image-based match of a person’s photo against a government record. The second part is expected to come online this year and is the Face Identification Service (FIS), a one-to-many, image match of an unknown person against multiple government records to help establish their identity. Critics are concerned at the false positives that similar technologies have found elsewhere like the US and their failure to prevent mass shootings.

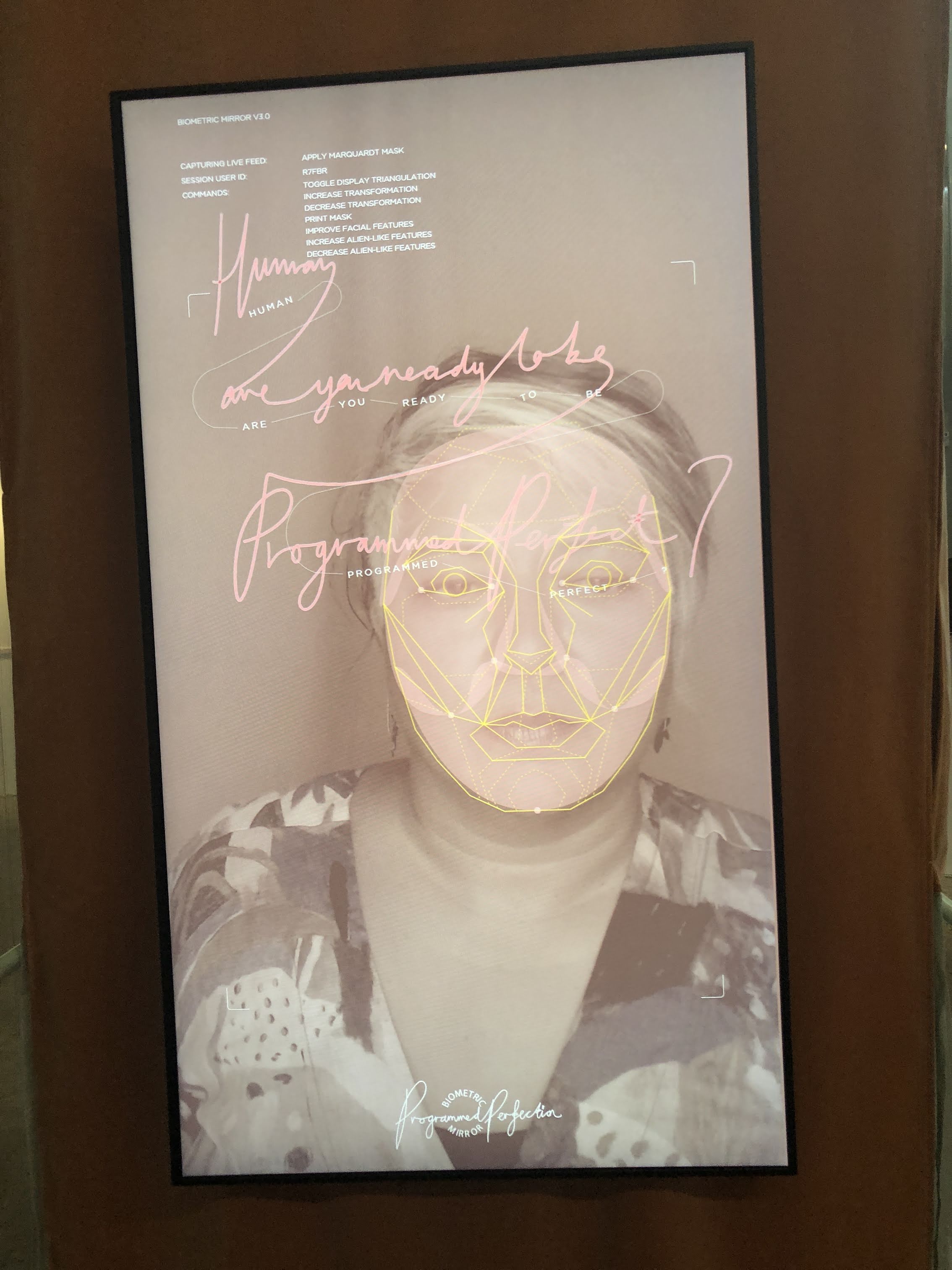

Me checking out the biometric mirror an artificial intelligence (AI) system to detect and display people’s personality traits and physical attractiveness based solely on a photo of their face. Project led by Dr Niels Wouters from the Centre for Social Natural User Interfaces (SocialNUI) and Science Gallery Melbourne at University of Melbourne.

Context is also important when considering secondary use of data. Indigenous voices like Kukutai observe that openness is not only a cultural issue but a political one, which has the potential to reinforce discourses of deficit. Privacy also has nuance here, public sharing does not indicate acceptance of subsequent use. Group privacy is also important for those groups who are on the receiving end of discriminatory data-driven policies. Open data can be used to improve the health and well being of individuals and communities. The efficiencies and effectiveness of health services can also be improved. Open data can also be used to challenge exclusionary policies and practices, however consideration must be given to digital literacy, privacy and how conditions of inequity might be exacerbated. Importantly, ensuring that structural changes occur that increase the access for all people to the determinants of health.

References

- Eubanks V. Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor. St. Martin’s Press, 2018.

- Faife C. The government wants your medical data. The Outline, https://theoutline.com/post/4754/the-government-wants-your-medical-data (2018, accessed 16 October 2018).

- Ferryman K, Pitcan M. Fairness in Precision Medicine. Data and Society, https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Data.Society.Fairness.In_.Precision.Medicine.Feb2018.FINAL-2.26.18.pdf (2018).

- González-Bailón S. Social science in the era of big data. POI 2013; 5: 147–160.

- Kostkova P, Brewer H, de Lusignan S, et al. Who Owns the Data? Open Data for Healthcare. Front Public Health 2016; 4: 7.

- Kowal E, Meyers T, Raikhel E, et al. The open question: medical anthropology and open access. Issues 2015; 5: 2.

- Krumholz HM, Waldstreicher J. The Yale Open Data Access (YODA) project—a mechanism for data sharing. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 403–405.

- Kukutai T, Taylor J. Data sovereignty for indigenous peoples:current practice and future needs. In: Kukutai T TaylorJ , ed. Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda. Acton,Australia: ANU Press; 2016: 1–22

- Lubet S. How a study about Chronic Fatigue Syndrome was doctored, adding to pain and stigma. The Conversation, 2017, http://theconversation.com/how-a-study-about-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-was-doctored-adding-to-pain-and-stigma-74890 (2017, accessed 22 October 2018).

- Pitcan M. Technology’s Impact on Infrastructure is a Health Concern. Data & Society: Points, https://points.datasociety.net/technologys-impact-on-infrastructure-is-a-health-concern-6f1ffdf46016 (2018, accessed 16 October 2018).

- Redden J. The Harm That Data Do. Scientific American, 2018, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-harm-that-data-do/ (2018, accessed 22 October 2018).

- Tennant M, Dyson K, Kruger E. Calling for open access to Australia’s oral health data sets. Croakey, https://croakey.org/calling-for-open-access-to-australias-oral-health-data-sets/ (2014, accessed 15 October 2018).

- Verhulst S, Noveck BS, Caplan R, et al. The Open Data Era in Health and Social Care: A blueprint for the National Health Service (NHS England). http://www.thegovlab.org/static/files/publications/nhs-full-report.pdf (May 2014).

- Yurkiewicz I. Paper Trails: Living and Dying With Fragmented Medical Records. Undark, https://undark.org/article/medical-records-fragmentation-health-care/ (2018, accessed 23 October 2018).

- Zook M, Barocas S, Crawford K, et al. Ten simple rules for responsible big data research. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13: e1005399.