On 15 February 2016, I spoke on 612 ABC Brisbane Afternoons with Kelly Higgins-Devine about cultural appropriation and privilege. Our discussion was followed by discussion with guests: Andie Fox – a feminist and writer; Carol Vale a Dunghutti woman; and Indigenous artist, Tony Albert. I’ve used the questions asked during the interview as a base for this blog with thanks to Amanda Dell (producer).

Why has it taken so long for the debate to escape academia to be something we see in the opinion pages of publications now?

Social media and online activism have catapulted questions about identities and politics into our screen lives. Where television allowed us to switch the channel, or the topic skilfully changed at awkward moments in work or family conversations, our devices hold us captive. Simply scrolling through our social media feeds can encourage, enrage or mobilise us into fury or despair. Whether we like it or not, as users of social media we are being interpolated into the complex terrain of identity politics. Merely sharing a link on your social media feed locates you and your politics, in ways that you might never reveal in real time social conversations. ‘Sharing’ can have wide ranging consequences, a casual tweet before a flight resulted in Justine Sacco moving from witty interlocutor to pariah in a matter of hours. The merging of ‘private’ and public lives never being more evident.

How long has the term privilege been around?

The concept of privilege originally developed in relation to analyses of race and gender but has expanded to include social class, ability level, sexuality and other aspects of identity. Interestingly, Jon Greenberg points out that although people of color have fought racism since its inception, the best known White Privilege educators are white (Peggy McIntosh, Tim Wise and Robin DiAngelo). McIntosh’s 1988 paper White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences through Work in Women’s Studies extended a feminist analysis of patriarchal oppression of women to that of people of color in the United States. This was later shortened into the essay White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (pdf), which has been used extensively in a a range of settings because of it’s helpful list format .

Many people have really strong reactions to these concepts – why is that?

Robin DiAngelo, professor of multicultural education and author of What Does it Mean to Be White? Developing White Racial Literacy developed the term ‘white fragility’ to identify:

a state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress becomes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves. These moves include outward display of emotions such as anger, fear and guilt, and behaviors such as argumentation, silence and leaving the stress-inducing situation

DiAngelo suggests that for white people, racism or oppression are viewed as something that bad or immoral people do. The racist is the person who is verbally abusive toward people of color on public transport, or a former racist state like apartheid South Africa. If you see yourself as a ‘good’ person then it is painful to be ‘called out’, and see yourself as a bad person. Iris Marion Young’s work useful. She conceptualises oppression in the Foucauldian sense as:

the disadvantage and injustice some people suffer not because of a tyrannical power coerces them but because of the everyday practices of a well-intentioned liberal society…

Young points out the actions of many people going about their daily lives contribute to the maintenance and reproduction of oppression, even as few would view themselves as agents of oppression. We cannot avoid oppression, as it is structural and woven throughout the system, rather than reflecting a few people’s choices or policies. Its causes are embedded in the unquestioned norms, habits, symbols and assumptions underlying institutional rules and the collective consequences of following those rules (Young, 1990). Seeing oppression as the practices of a well intentioned liberal society removes the focus from individual acts that might repress the actions of others to acknowledging that “powerful norms and hierarchies of both privilege and injustice are built into our everyday practices” (Henderson & Waterstone, 2008, p.52). These hierarchies call for structural rather than individual remedies.

We probably need to start with privilege – what does that term mean?

McIntosh identified how she had obtained unearned privileges in society just by being White and defined white privilege as:

an invisible package of unearned assets which I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I am meant to remain oblivious (p. 1).

Her essay prompted understanding of how one’s success is largely attributable to one’s arbitrarily assigned social location in society, rather than the outcome of individual effort.

“I got myself where I am today. Honestly, it’s not that hard. I think some people are just afraid of a little hard work and standing on their own two feet, on a seashell, on a dolphin, on a nymph-queen that are all holding them up.”

From: The Birth of Venus: Pulling Yourself Out Of The Sea By Your Own Bootstraps by Mallory Ortberg

McIntosh suggested that white people benefit from historical and contemporary forms of racism (the inequitable distribution and exercise of power among ethnic groups) and that these discriminate or disadvantage people of color.

How does privilege relate to racism, sexism? Are they the same thing?

It’s useful to view the ‘isms’ in the context of institutional power, a point illustrated by Sian Ferguson:

In a patriarchal society, women do not have institutional power (at least, not based on their gender). In a white supremacist society, people of color don’t have race-based institutional power.

Australian race scholars Paradies and Williams (2008) note that:

The phenomenon of oppression is also intrinsically linked to that of privilege. In addition to disadvantaging minority racial groups in society, racism also results in groups (such as Whites) being privileged and accruing social power. (6)

Consequently, health and social disparities evident in white settler societies such as New Zealand and Australia (also this post about Closing the gap) are individualised or culturalised rather than contextualised historically or socio-economically. Without context white people are socialized to remain oblivious to their unearned advantages and view them as earned through merit. Increasingly the term privilege is being used outside of social justice settings to the arts. In a critique of the Hottest 100 list in Australia Erin Riley points out that the dominance of straight, white male voices which crowds out women, Indigenous Australians, immigrants and people of diverse sexual and gender identities. These groups are marginalised and the centrality of white men maintained, reducing the opportunity for empathy towards people with other experiences.

Do we all have some sort of privilege?

Yes, depending on the context. The concept of intersectionality by Kimberlé Crenshaw is useful, it suggests that people can be privileged in some ways and not others. For example as a migrant and a woman of color I experience certain disadvantages but as a middle class cis-gendered, able-bodied woman with a PhD and without an accent (only a Kiwi one which is indulged) I experience other advantages that ease my passage through the world You can read more in the essay Explaining White Privilege to a Broke White Person.

How does an awareness of privilege change the way a society works?

Dogs and Lizards: A Parable of Privilege by Sindelókë is a helpful way of trying to understand how easy it is not to see your own privilege and be blind to others’ disadvantages. You might have also seen or heard the phrase ‘check your privilege’ which is a way of asking someone to think about their own privilege and how they might monitor it in a social setting. Exposing color blindness and challenging the assumption of race-neutrality is one mechanism for addressing the issue of privilege and its obverse oppression. Increasingly in health and social care, emphasis is being placed on critiquing how our own positions contribute to inequality (see my chapter on cultural safety), and developing ethical and moral commitments to addressing racism so that equality and justice can be made possible. As Christine Emba notes “There’s no way to level the playing field unless we first can all see how uneven it is.” One of the ways this can be done is through experiencing exercises like the Privilege Walk which you can watch on video. Jenn Sutherland-Miller in Medium reflects on her experience of it and proposes that:

Instead of privilege being the thing that gives me a leg up, it becomes the thing I use to give others a leg up. Privilege becomes a way create equality and inclusion, to right old wrongs, to demand justice on a daily basis and to create the dialogue that will grow our society forward.

Is privilege something we can change?

If we move beyond guilt and paralysis we can use our privilege to build solidarity and challenge oppression. Audra Williams points out that a genuine display of solidarity can require making a personal sacrifice. Citing the example of Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, where in challenging the director of a commercial about the lack of women with speaking roles, he ends up not being in the commercial at all when it is re-written with speaking roles for women. Ultimately privilege does not gets undone through “confession” but through collective work to dismantle oppressive systems as Andrea Smith writes.

Cultural appropriation is a different concept, but an understanding of privilege is important, what is cultural appropriation?

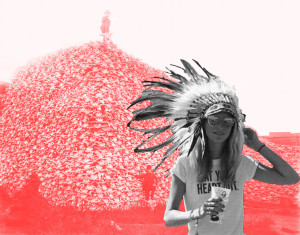

Cultural appropriation is when somebody adopts aspects of a culture that is not their own (Nadra Kareem Little). Usually it is a charge levelled at people from the dominant culture to signal power dynamic, where elements have been taken from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by the dominant group. Most critics of the concept are white (see white fragility). Kimberly Chabot Davis proposes that white co-optation or cultural consumption and commodification, can be cross-cultural encounters that can foster empathy and lead to working against privilege among white people. However, an Australian example of bringing diverse people together through appropriation backfired, when the term walkabout was used for a psychedelic dance party. Using a deeply significant word for initiation rites, for a dance party was seen as disrespectful. The bewildered organiser was accused via social media of cultural appropriation and changed the name to Lets Go Walkaround. So, I think that it is always important to ask permission and talk to people from that culture first rather than assuming it is okay to use.

What is the line between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation?

Maisha Z. Johnson cultural appreciation or exchange where mutual sharing is involved.

Can someone from a less privileged culture appropriate from the more privileged culture?

No, marginalized people often have to adopt elements of the dominant culture in order to survive conditions that make life more of a struggle if they don’t.

Does an object or symbol have to have some religious or special cultural significance to be appropriated?

Appropriation is harmful for a number of reasons including making things ‘cool’ for White people that would be denigrated in People of Color. For example Fatima Farha observes that when Hindu women in the United States wear the bindi, they are often made fun of, or seen as traditional or backward but when someone from the dominant culture wears such items they are called exotic and beautiful. The critique of appropriation extends from clothing to events Nadya Agrawal critiques The Color Run™ where you can:

run with your friends, come together as a community, get showered in colored powder and not have to deal with all that annoying culture that would come if you went to a Holi celebration. There are no prayers for spring or messages of rejuvenation before these runs. You won’t have to drink chai or try Indian food afterward. There is absolutely no way you’ll have to even think about the ancient traditions and culture this brand new craze is derived from. Come uncultured, leave uncultured, that’s the Color Run, promise.

The race ends with something called a “Color Festival” but does not acknowledge Holi. This white-washing (pun intended) eradicates everything Indian from the run including Holi, Krishna and spring. In essence as Ijeoma Oluo points out cultural appropriation is a symptom, not the cause, of an oppressive and exploitative world order which involves stealing the work of those less privileged. Really valuing people involves valuing their culture and taking the time to acknowledge its historical and social context. Valuing isn’t just appreciation but also considering whether the appropriation of intellectual property results in economic benefits for the people who created it. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar suggests that it is often one way:

One very legitimate point is economic. In general, when blacks create something that is later adopted by white culture, white people tend to make a lot more money from it… It feels an awful lot like slavery to have others profit from your efforts.

Loving burritos doesn’t make someone less racist against Latinos. Lusting after Bo Derek in 10 doesn’t make anyone appreciate black culture more… Appreciating an individual item from a culture doesn’t translate into accepting the whole people. While high-priced cornrows on a white celebrity on the red carper at the Oscars is chic, those same cornrows on the little black girl in Watts, Los Angeles, are a symbol of her ghetto lifestyle. A white person looking black gets a fashion spread in a glossy magazine; a black person wearing the same thing gets pulled over by the police. One can understand the frustration.

The appropriative process is also selective, as Greg Tate observes in Everything but the burden, where African American cultural properties including music, food, fashion, hairstyles, dances are sold as American to the rest of the world but with the black presence erased from it. The only thing not stolen is the burden of the denial of human rights and economic opportunity. Appropriation can be ambivalent, as seen in the desire to simultaneously possess and erase black culture. However, in the case of the appropriation of the indigenous in the United States, Andrea Smith declares (somewhat ironically), that the desire to be “Indian” often precludes struggles against genocide, or demands for treaty rights. It does not require being accountable to Indian communities, who might demand an end to the appropriation of spiritual practices.

Go West – Black: Random Coachella attendee, 2014. Red: Bison skull pile, South Dakota, 1870’s by Roger Peet.

Some people believe the cuisines of other cultures have been appropriated – is this an extreme example, or is it something we should consider?

The world of food can be such a potent site of transformation for social justice. I am a committed foodie (“somebody with a strong interest in learning about and eating good food who is not directly employed in the food industry” (Johnston and Baumann, 2010: 61). I am also interested in the politics of food. I live in Melbourne, where food culture has been made vibrant by the waves of migrants who have put pressure on public institutions, to expand and diversify their gastronomic offerings for a wider range of people. However, our consumption can naturalise and make invisible colonial and racialised relations. Thus the violent histories of invasion and starvation by the first white settlers, the convicts whose theft of food had them sent to Australia and absorbed into the cruel colonial project of poisoning, starving and rationing indigenous people remain hidden from view. So although we might love the food we might not care about the cooks at all as Rhoda Roberts Director of the Aboriginal Dreaming festival observed in Elspeth Probyn’s excellent book Carnal Appetites:

In Australia, food and culinary delights are always accepted before the differences and backgrounds of the origin of the aroma are.

Lee’s Ghee is an interesting example of appropriation, she developed an ‘artisanal’ ghee product, something that has been made for centuries in South Asia.

Lee Dares was taking the fashion world by storm working as a model in New York when she realized her real passion was elsewhere. So, she made the courageous decision to quit her glamorous job and take some time to explore what she really wanted to do with her life. Her revelation came after she spent some time learning to make clarified butter, or ghee, on a farm in Northern India. Inspired, she turned to Futurpreneur Canada to help her start her own business, Lee’s Ghee, producing unique and modern flavours of this traditional staple of Southeast Asian cuisine and Ayurvedic medicine.

The saying “We are what we eat” is about not only the nutrients we consume but also to beliefs about our morality. Similarly ‘we’ are also what we don’t eat, so our food practices mark us out as belonging or not belonging to a group.So, food has an exclusionary and inclusionary role with affective consequences that range from curiosity, delight to disgust. For the migrant for example, identity cannot be taken for granted, it must be worked at to be nurtured and maintained. It becomes an active, performative and processual project enacted through consumption. With with every taste, an imagined diasporic group identity is produced, maintained and reinforced. Food preparation represents continuity through the techniques and equipment that are used which affirm family life, and in sharing this food hospitality, love, generosity and appreciation can be expresssed. However, the food that is a salve for the dislocated, lonely, isolated migrant also sets her apart, making her stand out as visibly, gustatorily or olfactorily different. The resource for her well being also marks her as different and a risk. If her food is seen as smelly, distasteful, foreign, violent or abnormal, these characteristics can be transposed to her body and to those bodies that resemble her. Dares attempt to reproduce food that is made in many households and available for sale in many ‘ethnic’ shops and selling it as artisanal, led to accusations of ‘colombusing’ — a term used to describe when white people claim they have discovered or made something that has a long history in another culture. Also see the critique by Navneet Alang in Hazlitt:

The ethnic—the collective traditions and practices of the world’s majority—thus works as an undiscovered country, full of resources to be mined. Rather than sugar or coffee or oil, however, the ore of the ethnic is raw material for performance and self-definition: refine this rough, crude tradition, bottle it in pretty jars, and display both it and yourself as ideals of contemporary cosmopolitanism. But each act of cultural appropriation, in which some facet of a non-Western culture is columbused, accepted into the mainstream, and commodified, reasserts the white and Western as norm—the end of a timeline toward which the whole world is moving.

If this is the first time someone has heard these concepts, and they’re feeling confused, or a bit defensive, what can they do to understand more about it?

Here are some resources that might help, videos, illustrations, reading and more.

White privilege

- Toby Morris has created a beautiful illustration of Privilege.

- A hilarious look at white male privilege by Elliot Kalan.

- Video White privilege glasses from Chicago Theological Seminar.

- 11 Common Ways White Folks Avoid Taking Responsibility for Racism in the US by Robin DiAngelo.

- A great edited book on whiteness in Australia: Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism By Aileen Moreton-Robinson

- McSweeney’s have some hilarious writing on privilege including: a humorous product review of the invisible backpack of white privilege from by Joyce Miller; Don’t worry, I checked my privilege by Elliot Kalan; Some relatively recent College grads discuss their maids by Ellie Kemper and Privilege-checking preambles of varying degrees of singularity by George Morony.

- 4 Ways White People Can Process Their Emotions Without Bringing the White Tears by Jennifer Loubriel.

- The fairest — and funniest — way to split a restaurant bill by Emily Badger·

- See the excellent work on privilege by the Whariki Research Group, Massey University, New Zealand.

- Read about the reductive seduction of other people’s problems.

- Read more about whiteness, in an interview with Robin DiAngelo.

- Tim Wise has tons of resources.

- Check your privilege at the door.

- View the Unequal Opportunity Race. Screened as part of the Black History Month program at Glen Allen High School in Glen Allen, Virginia.

- This piece by Ali Owens about 4 problematic statements White people make about race — and what to say instead is useful: “I Don’t See Color.” “All Lives Matter.” “If racism is still a problem, how come we have a black president?” “Reverse racism is real.”

- The eight ways of being white by Gillian Schutte examines Barnor Hesses’ work (about whiteness studies from a radical black perspective) outlining the eight categories of white identity.

- An interesting read about privilege in sport using the example of Maria Sharapova and Serena Williams: The Benefit of the Doubt: A Case Study On White Privilege.

- Whiteness as Metaprivilege.

- The Subtle Linguistics of Polite White Supremacy.

- If you’d like to try the group exercise on privilege adapted from the Horatio Alger exercise by Ellen Bettman, you can read the questions here.

- Oscar Kightley’s terrific take down of the myth of Maori privilege.

- Brown eye asking about whether Maori seats in New Zealand is privileging Maori.

- A sobering read Death by gentrification: the killing that shamed San Francisco | Rebecca Solnit.

Cultural appropriation

- Aarti Olivia has a lovely piece on when it is appropriate to wear Indian cultural items.

- An exploration of Orientalism & Asian cultural appropriation as found in American music by Ube Empress.

- A much-needed primer on cultural appropriation by Katie J.M. Baker.

- More about food and cultural appropriation by Niya Bajaj.

- Check out this exploration of visual and auditory appropriation in US culture by Portland artist Roger Peet, featuring local residents.

- A critique of appropriation in fashion, Valentino’s African summer in Parallel magazine.

- I’ve written about cultural consumption in this piece on food and festivals, also about the white saviour complex and moving from being a bystander to an ally.

- A useful explanation on the meaning of a Native American headdress and why not to wear one.

- Brilliant piece by Texta Queen on cultural appropriation, white privilege and art on the fabulous Peril site.

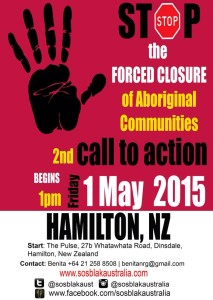

The view expressed by Tony Abbott (Prime Minister and the Minister for Indigenous Affairs), that taxpayers shouldn’t be expected to fund the “lifestyle choices” of Aboriginal people living in remote regions in support of Colin Barnett’s (West Australian Premier) decision to close 150 remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia reflects the repetition of the colonial project and Aboriginal dispossession. One of the mythologies of a white settler society is that white people are the first to arrive and develop the land, with colonisation a benign force (rather than one enacted through the processes of conquest and genocide and displacing the indigenous (Razack, 2002)). Closing the community draws attention away from governmental failures to ‘Close the Gap’ and instead displaces the blame on the supposed inadequacies and problems of Aboriginal communities (Amy McQuire) thereby individualising socio-political inequalities rather than revealing them as historic and structural. The paternalism of closing the communities “for their own good” and for the common good, appears benign but hides the brutality of forced removal and in doing so denies the significance of indigeneity as Mick Dodson notes:

It is not a “lifestyle choice” to be be born in and live in a remote Aboriginal community. It is more a decision to value connection to country, to look after family, to foster language and celebrate our culture. There are significant social, environmental and cultural benefits for the entire nation that flow from those decisions.

The protests against this cruel action have resounded around the world and have resonated in Aotearoa where I have lived for most of my life although I now live in the lands of the Kulin Nations in Gippsland as a migrant. As a nurse educator and researcher I am shaped by colonialism’s continuing effects in the white settler nation of Australia.

Nurses have often played an important part in social justice. Recently nursing professional bodies made a stand against violent state practices with the Australian College of Nursing (ACN) and Maternal Child and Family Health Nurses Australia (MCaFHNA) supporting The Forgotten Children report by the Australian Human Rights Commission against detaining children in immigration detention centres. Others like Chris Wilson wrote in Crikey about the many limitations of the Northern Territory Intervention:

I am saddened that the intervention has wasted so many resources, given so little support or recognition to the workers on the ground, paid so little attention to years of reports and above all involved absolutely no consultation with anyone, especially community members. The insidious effect of highlighting child abuse over all the other known problems in Aboriginal health is destructive to male health, mental health and community health, is unfounded in fact and is based in the inherent ignorance of this racist approach.

It has made me think about how nurses and midwives don’t often problematise our locations and consider our responsibilities within a social context of the discursive and material legacies of colonialism, neoliberalism, austerity and ‘othering’ (of Muslims, of refugees of Indigenous people) and “the ways in which we are complicitous in the subordination of others” (Razack, 1998, p.159). As Razack notes, groups that see themselves as apolitical must call into question their roles as “innocent subjects, standing outside of hierarchical social relations, who are not accountable for the past or implicated in the future” (Razack, 1998, p.10).

Colonisation and racism have been unkind to Indigenous people (term often used to refer to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples) with the health status of Indigenous people often compared to that of a developing country as I have pointed out elsewhere. The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage 2014 report measures the wellbeing of Australia’s Indigenous peoples. Briefly, Indigenous people:

- Experience social and health inequalities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2004).

- Are over represented and experience a higher burden of disease and higher mortality at younger ages than non-Indigenous Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2012b).

So, the question for me as a researcher and educator are what responsibility do nurses and the discipline of nursing have to Aboriginal health?

1) Recognise colonisation as a determinant of health

Indigenous people enjoyed better health in 1788 than people in Europe, they had autonomy over their lives, (ceremonies, spiritual practices, medicine, social relationships, management of land, law, and economic activities), but also didn’t suffer from illnesses that were endemic in18th century Europe. They didn’t have smallpox, measles, influenza, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, venereal syphilis and gonorrhoea. However, they were known to have suffered from; hepatitis B; some bacterial infections; some intestinal parasites; trauma; anaemia; arthritis; periodontal disease; and tooth attrition.

What’s often difficult for many nurses and students to imagine is that the past could have anything to do with the present, however, research in other settler colonial societies shows a clear relationship between social disadvantages experienced by Indigenous people and current health status. Colonisation and the spread of non-Indigenous peoples saw the introduction of illness (eg smallpox); the devaluing of culture; the destruction of traditional food base; separation from families; dispossession of whole communities. Furthermore, the ensuing loss of autonomy undermined social vitality, reduced resilience and created dispossession, demoralisation and poor health.

The negative impacts of colonisation on Indigenous led colonial authorities to try to ‘protect’ remaining Indigenous peoples, which saw the establishment of Aboriginal ‘protection’ boards (the first established in Victoria by the Aboriginal Protection Act of 18690. However, ‘protection’ imposed enormous restrictions eg living in settlements; forced separation of Indigenous children from their families. With between one-in-three and one-in-ten Indigenous children forcibly removed from their families and communities from 1910 until 1970. The result was irrevocable harm as one of the Stolen Generations stated:

We may go home, but we cannot relive our childhoods. We may reunite with our mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, aunties, uncles, communities, but we cannot relive the 20, 30, 40 years that we spent without their love and care, and they cannot undo the grief and mourning they felt when we were separated from them

- The Redfern Speech from December 1992 (Paul Keating Australian Prime Minister publicly acknowledging to Indigenous Australians that European settlers were responsible for difficulties Australian Aboriginal communities face).

- The Bring them home report: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families 1997 recommended that the Prime Minister apologise to the Stolen Generations, however John Howard refused to do so. Sorry Day evolved as a result.

- It was only on February 13th, 2008 that Kevin Rudd issued the National Apology Speech, some of which is excerpted below:

For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry. To the mothers and the fathers, the brothers and the sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry. And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry.

Also watch Babakiueria which uses role reversal to satirise and critique Australia’s treatment of its Indigenous peoples. Aboriginal actors play the colonisers, while white actors play the indigenous Babakiuerians.

2) Recognise continuing colonial practices

This blog started with the news of the closures of 150 remote Aboriginal communities in WA. Only one example of continuing colonial practices. Mick Dodson suggests that the closure of the 150 WA communities reflects an inability of the descendants of settlers to:

negotiate in a considered way the right of Aboriginal people to live as Aboriginal peoples in our own lands and seas, while also participating in every aspect of life as contemporary Australian citizens.

You can also read about proposed alternatives to the closure by Rebecca Mitchell.

3) Develop an understanding of racism as a determinant of health

Racism (racial discrimination) is linked with colonisation and oppression and is a social determinant of health. Nancy Krieger (2001) defines it as a process by which members of a socially defined racial group are treated unfairly because of membership of that group. Too often racism is seen as individual actions rather than as structural and embedded as this video shows. We know that racism damages health and in the health sector health systems and service providers can perpetuate Aboriginal health care disparities through attitudes and practices (Durey).

Anti-racist scholars suggest that there are three levels of racism in health.

- Institutional: Practices, policies or processes experienced in everyday life which maintain and reproduce avoidable and unfair inequalities across ethnic/racial groups (also called systemic racism);

- Interpersonal, in interactions between individuals either within their institutional roles or as private individuals;

- Internalised, where an individual internalises attitudes, beliefs or ideologies about the inferiority of their own group.

Krieger and others have written extensively about how racism affects health. People who experience racism experience the following:

- Inequitable and reduced access to the resources required for health;

- Inequitable exposure to risk factors associated with ill-health;

- Stress and negative emotional/cognitive reactions which have negative impacts on mental health as well as affecting the immune, endocrine, cardiovascular and other physiological systems;

- Engagement in unhealthy activities and disengagement from healthy activities

1 in 3 Aboriginal Victorians experienced racism in a health care setting according to a VicHealth survey. The respondents reported:

- Poorer health status;

- Lower perceived quality of care;

- Under-utilisation of health services;

- Delays in seeking care;

- Failure to follow recommendations;

- Societal distrust;

- interruptions in care;

- Mistrust of providers;

- Avoidance of health care systems.

This video on understanding the impact of racism on Indigenous child health by Dr Naomi Priest is well worth a look.

4) Develop a collective understanding of health and the importance of cultural determinants of health

Health is defined in the National Aboriginal Health Strategy (1989) as:

Not just the physical well-being of the individual but the social, emotional and cultural well-being of the whole community. This is a whole of life view and it also includes the cyclical concept of life-death-life

It is important that in considering the issues of colonisation, racism and inter-generational trauma that the diverse cultures and histories of indigenous people are not viewed through a deficit lens. So often mainstream media reinforce the myth that responsibility for poor health (whether it’s about people who drink, are obese or smoke) is an individual and group one rather than linked with social determinants including colonisation, economic restructuring or the devastating social consequences of state neoliberal policies. As Professor Ngiare Brown notes, there are significant cultural determinants of health which should be supported including:

- Self-determination; Freedom from discrimination;

- Individual and collective rights;

- Freedom from assimilation and destruction of culture;

- Protection from removal/relocation;

- Connection to, custodianship, and utilisation of country and traditional lands;

- Reclamation, revitalisation, preservation and promotion of language and cultural practices;

- Protection and promotion of Traditional Knowledge and Indigenous Intellectual Property; and

- Understanding of lore, law and traditional roles and responsibilities.

5) Develop an understanding of the organisations, policies, levers and strategies that are available to support Indigenous wellbeing

- Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs), which are primary health care services operated by local Aboriginal communities to deliver holistic, comprehensive, and culturally appropriate health care. There are over 150 ACCHSs in urban, regional and remote Australia.

- Close the gap campaign targets (also see a recent blogpost) developed by a consortium of 40 of Australia’s leading Indigenous and non-Indigenous health peak bodies and human rights organisations, which calls on Australian governments to commit to achieving Indigenous health equality within 25 years.

- 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Article 24 of which points out that Indigenous people have the right “to access, without any discrimination, [to] all social and health services” and “have an equal right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. States shall take the necessary steps with a view to achieving progressively full realisation of this right”.

- Become familiar with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-2023.

- Support the WHO Closing the gap in a generation, which recommends three actions for improving the world’s health:

- Improve the conditions of daily life – the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age.

- Tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources – the structural drivers of those conditions of daily life – globally, nationally, and locally.

- Measure the problem, evaluate action, expand the knowledge base, develop a workforce that is trained in the social determinants of health, and raise public awareness about the social determinants of health.

- Support the Australian Nursing Code of Ethics statement:

In recognising the linkages and operational relationships that exist between health and human rights, the nursing profession respects the human rights of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the traditional owners of this land, who have ownership of and live a distinct and viable culture that shapes their world view and influences their daily decision making. Nurses recognise that the process of reconciliation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-indigenous Australians is rightly shared and owned across the Australian community. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, while physical, emotional, spiritual and cultural wellbeing are distinct, they also form the expected whole of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander model of care

6) Becoming a critical, reflexive, knowledgeable nurse who legitimates the cultural rights, values and expectations of Aboriginal people

More than ever, social justice provides a valuable lens for nursing practice (see Sir Michael Marmot’s speech). Cultural competence and safety directly reduce health disparities experienced by Indigenous Australians (Lee et al., 2006; Durey, 2010). It makes sense that the safer the health care system and its workers are, the more likely Indigenous people are to engage and use the services available. Early engagement in the health care system results in early health intervention strategies, prevention of illness and improved overall health outcomes for Indigenous Australians. The key features of cultural competence identified in the Cultural diversity plan for Victoria’s specialist mental health services 2006-2010 are:

- Respectful and non-judgemental curiosity about other cultures, and the ability to seek cultural knowledge in an appropriate way;

- Tolerance of ambiguity and ability to handle the stress of ambiguous situations;

- Readiness to adapt behaviours and communicative conventions for intercultural communication.

Nurses have a role in improving health outcomes, but this requires an understanding of the reasons why there are higher morbidity and mortality rates in Indigenous populations than in the general population. It requires that nurses engage in reflection and interrogate the existing social order and how it reproduces discriminatory practices in structural systems such as health care, in institutions and in health professionals (Durey, 2010). It’s important that as nurses we focus on our own behaviour, practice and skills both as professionals and individuals working in the health system.

I think this statement about Cultural security from the Department of Health, Western Australian Health (2003) Aboriginal Cultural Security: A background paper, page 10. is a valuable philosophy of practice:

Commitment to the principle that the construct and provision of services offered by the health system will not compromise the legitimate cultural rights, values and expectations of Aboriginal people. It is a recognition, appreciation and response to the impact of cultural diversity on the utilisation and provision of effective clinical care, public health and health system administration

To conclude, I leave the last words to Professor Ngiare Brown:

We represent the oldest continuous culture in the world, we are also diverse and have managed to persevere despite the odds because of our adaptability, our survival skills and because we represent an evolving cultural spectrum inclusive of traditional and contemporary practices. At our best, we bring our traditional principles and practices – respect, generosity, collective benefit, collective ownership- to our daily expression of our identity and culture in a contemporary context. When we are empowered to do this, and where systems facilitate this reclamation, protection and promotion, we are healthy, well and successful and our communities thrive.

References

Universities of Australia. (2011). National best practice framework for indigenous cultural competency in Australian Universities.

Awofeso, N. (2011). Racism: A major impediment to optimal indigenous health and health care in Australia. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin, 11(3), 1-8.

Best, O., & Stuart, L. (2014). An Aboriginal nurse-led working model for success in graduating indigenous Australian nurses. Contemporary Nurse, 4082-4101.

Chapman, R., Smith, T., & Martin, C. (2014). Qualitative exploration of the perceived barriers and enablers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people accessing healthcare through one victorian emergency department. Contemporary Nurse.

Christou, A., & Thompson, S. C. (2012). Colorectal cancer screening knowledge, attitudes and behavioural intention among indigenous western Australians. BMC Public Health, 12, 528. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-528

Downing, R., & Kowal, E. (2010). Putting indigenous cultural training into nursing practice. Contemporary Nurse, 37(1), 10-20. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.010

Durey, A. (2010). Reducing racism in Aboriginal health care in Australia: Where does cultural education fit? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 34 Suppl 1, S87-92. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00560.x

Durey, A., Lin, I., & Thompson, D. (2013). It’s a different world out there: Improving how academics prepare health science students for rural and indigenous practice in Australia. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(5), 722-733.

Haynes, E., Taylor, K. P., Durey, A., Bessarab, D., & Thompson, S. C. (2014). Examining the potential contribution of social theory to developing and supporting Australian indigenous-mainstream health service partnerships. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 75. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0075-5

Herk, K. A. V., Smith, D., & Andrew, C. (2014). Identity matters: Aboriginal mothers’ experiences of accessing health care. Contemporary Nurse. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.057

Hunt, L., Ramjan, L., McDonald, G., Koch, J., Baird, D., & Salamonson, Y. (2015). Nursing students’ perspectives of the health and healthcare issues of Australian indigenous people. Nurse Education Today, 35(3), 461-7. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2014.11.019

Kelly, J., West, R., Gamble, J., Sidebotham, M., Carson, V., & Duffy, E. (2014). ‘She knows how we feel’: Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander childbearing women’s experience of continuity of care with an Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander midwifery student. Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 27(3), 157-62. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2014.06.002

Kildea, S., Kruske, S., Barclay, L., & Tracy, S. (2010). Closing the gap: How maternity services can contribute to reducing poor maternal infant health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Rural and Remote Health, 10(1383), 9-12.

Kowal, E. (2008). The politics of the gap: Indigenous Australians, liberal multiculturalism, and the end of the self-determination era. American Anthropologist, 110(3), 338-348.

Larson, A., Gillies, M., Howard, P. J., & Coffin, J. (2007). It’s enough to make you sick: The impact of racism on the health of Aboriginal Australians. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 31(4), 322-329.

Liaw, S. T., Lau, P., Pyett, P., Furler, J., Burchill, M., Rowley, K., & Kelaher, M. (2011). Successful chronic disease care for Aboriginal Australians requires cultural competence. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 35(3), 238-48. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00701.x

Nash, R., Meiklejohn, B., & Sacre, S. (2006). The Yapunyah project: Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in the nursing curriculum. Contemporary Nurse, 22(2), 296-316. doi:10.5172/conu.2006.22.2.296

Nielsen, A. M., Stuart, L. A., & Gorman, D. (2014). Confronting the cultural challenge of the whiteness of nursing: Aboriginal registered nurses’ perspectives. Contemporary Nurse, 48(2), 190-6. doi:10.5172/conu.2014.48.2.190

Paradies, Y. (2005). Anti-Racism and indigenous Australians. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 5(1), 1-28.

Paradies, Y., & Cunningham, J. (2009). Experiences of racism among urban indigenous Australians: Findings from the DRUID study. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(3), 548-573. doi:10.1080/01419870802065234

Paradies, Y., Harris, R., & Anderson, I. (2008). The impact of racism on indigenous health in Australia and aotearoa: Towards a research agenda. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health Darwin.

Pedersen, A., Beven, J., Walker, I., & Griffiths, B. (2004). Attitudes toward indigenous Australians: The role of empathy and guilt. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 14(4), 233-249. doi:10.1002/casp.771

Pedersen, A., Dudgeon, P., Watt, S., & Griffiths, B. (2006). Attitudes toward indigenous Australians: The issue of special treatment. Australian Psychologist, 41(2), 85-94. Pijl-Zieber, E. M., & Hagen, B. (2011). Towards culturally relevant nursing education for Aboriginal students. Nurse Education Today, 31(6), 595-600. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.014Prior, D. (2009). The meaning of cancer for Australian Aboriginal women; changing the focus of cancer nursing. European Journal of Oncology Nursing : The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 13(4), 280-6. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2009.02.005

Rigby, W., Duffy, E., Manners, J., Latham, H., Lyons, L., Crawford, L., & Eldridge, R. (2010). Closing the gap: Cultural safety in indigenous health education. Contemporary Nurse, 37(1), 21-30. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.021

Rix, E. F., Barclay, L., Wilson, S., & Barclay, E. R. L. (2014). Can a white nurse get it?Reflexive practiceand the non-indigenous clinician/researcher working with Aboriginal people. Rural Remote Health, 4, 2679.

Stuart, L., & Nielsen, A. -M. (2014). Two Aboriginal registered nurses show us why black nurses caring for black patients is good medicine. Contemporary Nurse. doi:10.5172/conu.2011.37.1.096

Szoke, H. (2012). National anti-racism strategy. Australian Human Rights Commission.

Thackrah, R. D., & Thompson, S. C. (2014). Confronting uncomfortable truths: Receptivity and resistance to Aboriginal content in midwifery education. Contemporary Nurse. doi:10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.113

Thackrah, R. D., Thompson, S. C., & Durey, A. (2014). “Listening to the silence quietly”: Investigating the value of cultural immersion and remote experiential learning in preparing midwifery students for clinical practice. BMC Research Notes, 7, 685. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-685

Williamson, M., & Harrison, L. (2010). Providing culturally appropriate care: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(6), 761-9. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.012

Ziersch, A. M., Gallaher, G., Baum, F., & Bentley, M. (2011a). Responding to racism: Insights on how racism can damage health from an urban study of Australian Aboriginal people. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 73(7), 1045-53. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.058

Last week I visited the Tasman Peninsula in Tasmania, which was the country of the Pydairrerme band of the Oyster Bay tribe, before being invaded and settled by Europeans. As a a recent arrival in Australia (from New Zealand in 2013), I see it as my responsibility to develop a local nuanced understanding of settler-colonialism, the dispossession of indigenous Aboriginal people and the colonial carceral system. Port Arthur, a convict settlement for the former colony of Van Diemen’s Land on the Tasman Peninsula was on my itinerary. Maria M. Tumarkin points out that places like Port Arthur with their material remnants allow us to engage with events (like the trauma of convictism) and to experience the hardship and suffering endured by convicts without actually putting ourselves on the line. People that visit sites of trauma or traumascapes as Tumarkin calls them (also known as dark tourism (Philip Stone), thanatourism (A.V. Seaton), trauma tourism (Laurie Beth Clark) are not either “voyeuristic tourists” or “earnest pilgrims” but can also have mixed motives, some unknown to them. I wanted to better understand the colonial and convict history of my adopted homeland, especially because my partner is Australian born and has an ancestral convict history.

Port Arthur has a history of prison tourism and its sandstone, pink brick and weatherboard buildings along a beautiful cove, belie it’s disciplinary role for convicts from 1830-1877. Prior to 1840, convicts were used as colonial labour for settlers, after 1840 convicts undertook a trial period of labour in a government gang, and if this was satisfactory could then be hired out to the private sector. This partnership with the private sector transferred costs of rations, clothing and accommodation from the colonial government to private masters who did not pay wages (sound familiar?). Thus, Van Diemen’s Land was a panopticon without walls rather than a prison. More about panopticons later! For people that “abused” this “open” punishment or for whom a suitable assignment could not be found, a place of secondary punishment was needed. Hence the development of the penal station of Port Arthur to house those who could not be assigned and where labour could be extracted and the recalcitrant punished as Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart notes. After the closure of the penal station, decline and damage to the carceral buildings of Port Arthur ensued. Renewed interest in the late 1920s, saw restoration work begin so that the tourism potential of the site could be maximised. In the 1980s Port Arthur became Australia’s most famous open-air museum, and the 1996 killing of innocent people by an armed gunman did not diminish its role as a tourist site. A memorial garden now houses the Broad Arrow cafe where twenty of the thirty five victims were shot which represents a cathartic location -triggering powerful emotions.

The carceral buildings at Port Arthur including the Penitentiary and the Separate Prison in use nineteenth-century ideas about how adult deviants could be treated in order to transform them into skilled and docile members of society. Foucault used the metaphor of the panopticon designed by the philosopher Jeremy Bentham to talk about the change in society from a “culture of spectacle” (public displays of torture etc) to a “carceral culture.” where punishment and discipline became internalized. The panopticon was a prison designed so that a central observation tower could potentially view every cell and every prisoner. However, the prisoners could not view observers or guards, so prisoners could not tell if or when they were being observed. Consequently, they came to believe that they might be always being observed, and disciplined themselves into model prisoners. Port Arthur’s prison was shaped like a cross with exercise yards at each corner and prisoner wings connected to the surveillance core of the Prison from where each wing could be clearly seen, although individual cells could not (thus differing from the theory of the panopticon). Panopticism or the ever-present threat of potential or continual surveillance is a mechanism for translating technologies of disciplinary control into an individual’s everyday practices.

Reinforcing Islam and Muslims as ‘others’

This brings me to the key concern of this blog post, the events of December 15th when a single armed man took people hostage inside the Lindt Chocolate cafe in Sydney. His actions ultimately led to the death of two innocent people and overshadowed scrutiny of the mid-year budget update (which includes cuts to Foreign Aid and the Australian Human Rights Commission). The gunman had significant social and inter-personal problems but the media were quick to label the siege a terrorist attack (it was a Muslim person brandishing a flag after all) which also helped to justify future and recent past legislation limiting the movement of some groups of people. Only last week New Zealand politicians hastily passed anti-terror laws through Parliament. In the United Kingdom, PM David Cameron pointed out:

It demonstrates the challenge that we face of Islamist extremist violence all over the world. This is on the other side of the world (in Sydney) but it’s the sort of thing that could just as well happen here in the UK or in Europe.

Many media sources and other commentators were quick to jump to conclusions with The Daily Telegraph front page screaming “Death cult CBD attack” and anti Muslim scare mongering from shock jocks like Rad Hadley.

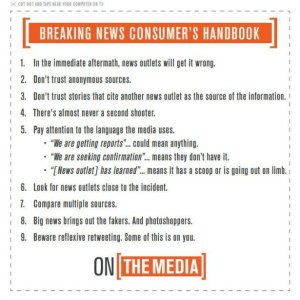

Interestingly the reportage focused on the religion of the gunman and brought out racist and inflammatory commentary from people on Twitter and Facebook. What was especially interesting was the way in which misinformation spread far and wide as Alex McKinnon carefully pointed out:

But the families of the people involved, and the broader public, have a right to information that is accurate and correct. Spreading rumours on something as potentially serious as this is not innocuous: it is actively harmful. Your best course of action is to refrain from commenting or spreading unchecked information, online or otherwise, until the facts are known, the situation is better understood and our collective emotions aren’t running so high.

In a critique of media coverage Bernard Keane of Crikey interrogated the language and phrases that proliferated in coverage:

The assumptions loaded into such “lost its innocence” statements merit entire theses; indeed, many have doubtless already been written. That Australia, established as a prison colony and forged in dispossession, genocide and gleeful participation in the long wars of imperialism throughout the 20th century, could be “innocent”; that it is such a fragile culture that a single moment of violence, however atypical, could comprehensively alter its very nature.

New Matilda predicted that there would be spike in violence against Muslims and mosques:

Just as Christian churches all over the nation were attacked in the immediate aftermath of the 1996 Port Arthur siege, Mosques around Australia will be vandalized. Because, naturally, if the siege is in fact being perpetrated by Muslim extremists, then all Muslims (and all symbols of Islam) are fair game.

Bernard Keane also predicted that media identities and journalists would:

disgrace themselves and their profession by reporting wild speculation as fact. When you’re reporting a big story on a 24 hours news cycle, and you have no idea what’s going on, you need to fill the gaps. Anything that moves is news, and if it doesn’t move, give it a push.

With the media finding:

some lone nut Muslim extremist somewhere to say something short of condemning the violence, and then portray that as the view of the broader Muslim population. Eventually, Australian media will start demanding that all Muslim leaders everywhere condemn the violence… even though Muslim leaders everywhere will have already condemned the violence.

This was an accurate prediction as in no time at all, the Australian Muslim community denounced the act:

However, Randa Abdel-Fattah problematised this gesture in the context of broader insatiable community demands:

Muslim organisations – weary, under-resourced, under pressure – were ready to condemn, to distance, to reassure because after 13 years of condemning, distancing, and reassuring, the Australian public seems to still be in doubt about Islam’s position on terrorism.

Australian responses give me hope…

As people gather to pay their respects in a very public way. I’d like to think that there’s an opportunity for healing rather than fomenting further hate and powerlessness. I agree with Tasmanian and Booker Prize winner Richard Flanagan’s observations of people:

I think evil, murder, hate… these things are as deeply buried within us as love, kindness, goodness and perhaps they are far more closely entwined than we would care to admit… And the face of evil is never the other, it’s always our face.

So with that in mind, I’d like to talk about the outpouring of grace, dignity, compassion and thoughtful analysis that I’ve also seen in abundance.

- Clover Moore Lord Mayor of Sydney:

- Victoria Rollison challenged media representations of the gunman and the framing of the siege as a Muslim issue:

“I was a teenager when the Port Arthur massacre happened, and I don’t recall there being a backlash at the time against white people with blonde hair. I’m a white person with blonde hair, and no one has ever heaped me into the ‘possibly a mass murderer’ bucket along with Martin Bryant. Or more recently, Norwegian Anders Breivik, who apparently killed 69 young political activists because he didn’t like their party’s immigration stance which he saw as too open to Islamic immigrants. In fact, in neither case do I recall the word ‘terrorist’ even being used to describe the mass murders of innocent people.”

- Clementine Ford similarly pointed out that Christianity has not come under the same scrutiny in other violent incidents, both in Australia and Norway, while also addressing the issue of violence against women:

Almost without fail, non-Muslim white men who behave as he did are given the benefit of individual autonomy. When Rodney Clavell staged a 13 hour siege at an Adelaide brothel in June of this year, his reported Christianity barely made any of the news reports. Where it did, it was in articles which spent a good proportion of time talking about how much of a good bloke he was. Norway’s Andres Breivik – a right wing Christian who murdered 77 people in 2011 – was frequently described as ‘a lone wolf’. His actions were certainly not treated as a defining characteristic of members of the Christian faith, nor did Christians have to fear backlash once his affiliation was revealed.

- Max Fisher responded:

This expectation we place on Muslims, to be absolutely clear, is Islamophobic and bigoted. The denunciation is a form of apology: an apology for Islam and for Muslims. The implication is that every Muslim is under suspicion of being sympathetic to terrorism unless he or she explicitly says otherwise. The implication is also that any crime committed by a Muslim is the responsibility of all Muslims simply by virtue of their shared religion. This sort of thinking — blaming an entire group for the actions of a few individuals, assuming the worst about a person just because of their identity — is the very definition of bigotry.

- The hashtag #illridewithyou (but also note Beyondblue’s national anti-discrimination campaign in 2014 which highlights the impact of discrimination on the social and emotional well-being of Aboriginal people which has not had the same flurry of support). Also some interesting critique from Eugenia Flynn who asks What happens when the ride Is over?

- Interfaith action from mosques, synagogues and churches inviting the public to gather for unity, and against violence, fear and hatred.

- Social media sharing guidelines from Alex McKinnon:

When in doubt, wait. When you are not in full possession of the facts, remain silent so that more informed voices can be heard

- Good to see some thought about the people who survived the siege and their recovery.

- Lastly, it’s great to see some critique of mass media practice from John Birmingham in the Canberra Times and Bernard Keane in Crikey.

Ending with a reflection

Thinking with sadness of all the people traumatized by yesterday’s events, the innocent people that lost their lives and all their loved ones in Sydney. Thinking also of people who live with and are caught up in acts of power, control and violence which are not of their own making globally. Thinking of the ways in which ‘our’ institutions serve ‘us’ and how responsibly they exercise their power and influence (police, media, politicians), whether their role creates calm, understanding, light or heat, marginalising and stereotyping. Whether the creation of an ‘other’ is necessary and what future it holds open for ‘others’ who experience heightened vigilance, policing and surveillance. Thinking of those who work for peace, who work to address injustice. Thinking of the need to not conclude too quickly, to not judge too harshly before understanding. Mostly today sending love, prayers and hope into the world in this season of peace and goodwill.

Nairn, DeSouza, Moewaka Barnes, Rankine, Borell, and McCreanor (2014). Nursing in media-saturated societies: implications for cultural safety in nursing practice in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Research in Nursing September 19: 477-487,doi:10.1177/1744987114546724

Great to be published in the Journal of Research in Nursing September 2014 issue on ‘Race’, Ethnicity and Nursing, Edited by: Lorraine Culley. I had the pleasure of being included in a previous issue in 2007, so it’s great to be in this one.

Abstract

This educational piece seeks to apprise nurses and other health professionals of mass media news practices that distort social and health policy development. It focuses on two media discourses evident in White settler societies, primarily Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, drawing out implications of these media practices for those committed to social justice and health equity. The first discourse masks the dominant culture, ensuring it is not readily recognised as a culture, naturalising the dominant values, practices and institutions, and rendering their cultural foundations invisible. The second discourse represents indigenous peoples and minority ethnic groups as ‘raced’ – portrayed in ways that marginalise their culture and disparage them as peoples. Grounded in media research from different societies, the paper focuses on the implications for New Zealand nurses and their ability to practise in a culturally safe manner as an exemplary case. It is imperative that these findings are elaborated for New Zealand and that nurses and other health professionals extend the work in relation to practice in their own society.

One of my favourite pieces of the article proposes some ways in which nurses can engage in critical assessment of mass media, by asking questions like:

- From whose point of view is this story told?

- Who is present?

- How are they named and/or described?

- Who, of those present, is allowed to give their interpretation of the matter?

- Who is absent?

- Whose interests are served by telling the story this way?

One of the things that I love about this journal is that they ask for commentaries from a reviewer. My former colleague Denise Wilson (Professor, Māori Health Taupua Waiora Centre for Māori Health Research/School of Public Health & Psychosocial Studies, National Institute of Public Health and Mental Health Research, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand), has reviewed our paper and says:

I would urge nurses to read this paper and reflect on how the media influences their own practice and engagement with minority and marginalised groups. Media portrayals of minority groups often reflect negatively geared dominant cultural sentiments, becoming ‘accepted’ fact within our communities. Nurses need to be aware that their efforts to be culturally safe in their practice can be undermined by the normalisation and acceptance of what is portrayed in the media. Therefore, nurses are encouraged by the authors to come together and question the ‘taken-for-granted’ dominant cultural media portrayals to create a stronger platform for culturally safe practice.

In August 2014 there was a wonderful story of how “people power” had freed a man in Perth, whose leg had become caught in the gap between a platform and train on his morning commute. You can watch the video here. What struck me about this story was that people taking part in their “regular” commute noticed something out of the ordinary and used their combined energy to free the man. Someone alerted the driver to make sure that the train didn’t move, staff then asked passengers to help and in tandem they rocked the train backwards from the platform so it tilted and his leg could be freed. It made me think about the gaps people are stuck in, that exist all around us, that have become so routine, that we are habituated to, and fail to notice.

One of the biggest gaps is in the health outcomes between Indigenous and non-indigenous people in settler nations. Oxfam notes that Australia equals Nepal for the world’s greatest life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. This is despite Australians enjoying one of the highest life expectancies of any country in the world. Indigenous Australians (who numbered 669,900 people in 2011, ie 3% of the total population) live 10-17 years less than other Australians. In the 35–44 age group, Indigenous people die at about 5 times the rate of non-Indigenous people. Babies born to Aboriginal mothers die at more than twice the rate of other Australian babies, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience higher rates of preventable illness such as heart disease, kidney disease and diabetes.

One of the most galvanising visions for addressing the health and social disparities between Indigenous and non-indigenous people is The Close the Gap campaign aiming to close the health and life expectancy gap between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians within a generation. By 2030 any Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child born in Australia will have the same opportunity as other Australian children to live a long, healthy and happy life.

Nurses play an important role in creating a more equitable society and have been forerunners in the field of cultural safety and competence. For the gap to close, nurses need an understanding of health that includes social, economic, environmental and historical relations. Cultural safety from Aotearoa New Zealand has been an invaluable tool for me as nurse for analysing this set of relations. However, as a newcomer to Australia, I have a lot to learn about what cultural competency means here and how I fulfil my responsibilities as a nurse educator to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. To that end, this blog piece focuses on some of the frameworks in nursing that might enable nurses to close the gap. I am particularly interested in frameworks that enable nurses to widen the lens of care beyond the individual and consider service users in the context of their families and communities and broader social and structural inequities. I’m also interested in policy frameworks that can support practice.

A social determinants of health approach takes into account “the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. These circumstances are in turn shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, and politics” (WHO, 2010). A health equity lens has also been invaluable to my own practice, it refers to the absence of systematic disparities in health (or in the major social determinants of health) between groups with different social advantage/disadvantage. Social inequalities refer to “relatively long-lasting differences among individuals or groups of people that have implications for individual lives” (McMullin, 2010, p.7). While an inequity, refers to an unjust distribution of resources and services. “equity means social justice” (see, Braverman 2003). The term “social and structural inequities,” refers to unfair and avoidable ways in which members of different groups in society are treated and/or their ability to access services.

Principle Four of the New Zealand Nursing Council: Guidelines for Cultural safety in Nursing and Midwifery Education (2011) pay great attention to the issue of power:

PRINCIPLE FOUR Cultural safety has a close focus on:

4.1 understanding the impact of the nurse as a bearer of his/her own culture, history, attitudes and life experiences and the response other people make to these factors

4.2 challenging nurses to examine their practice carefully, recognising the power relationship in nursing is biased toward the provider of the health and disability service

4.3 balancing the power relationships in the practice of nursing so that every consumer receives an effective service

4.4 preparing nurses to resolve any tension between the cultures of nursing and the people using the services

4.5 understanding that such power imbalances can be examined, negotiated and changed to provide equitable, effective, efficient and acceptable service delivery, which minimises risk to people who might otherwise be alienated from the service.

The Australian Code of Ethics for nurses and midwives in Australia also pays attention to the role of nurses in having a moral responsibility to protect and safe guard human rights as means to improving health outcomes and having concern for the structural and historical:

The nursing profession recognises the universal human rights of people and the moral responsibility to safeguard the inherent dignity and equal worth of everyone. This includes recognising, respecting and, where possible, protecting the wide range of civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights that apply to all human beings.

The nursing profession acknowledges and accepts the critical relationship between health and human rights and ‘the powerful contribution that human rights can make in improving health outcomes’. Accordingly, the profession recognises that accepting the principles and standards of human rights in health care domains involves recognising, respecting, actively promoting and safeguarding the right of all people to the highest attainable standard of health as a fundamental human right, and that ‘violations or lack of attention to human rights can have serious health consequences’.

In recognising the linkages and operational relationships that exist between health and human rights, the nursing profession respects the human rights of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the traditional owners of this land, who have ownership of and live a distinct and viable culture that shapes their world view and influences their daily decision making. Nurses recognise that the process of reconciliation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-indigenous Australians is rightly shared and owned across the Australian community. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, while physical, emotional, spiritual and cultural wellbeing are distinct, they also form the expected whole of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander model of care.

The Code stops short of using words like colonisation and racism, but the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation background paper “Creating the Cultural Safety Training Standards and Assessment Paper” (2011, p. 9) points out that awareness and sensitivity training, result in individuals becoming more aware of cultural, social and historical factors and engaging in self-reflection however if there isn’t an institutional response and the responsibilities for institutional racism remain individualised:

Even if racism is named, the focus is on individual acts of racial prejudice and racial discrimination. While historic overviews may be provided, the focus is again on the individual impact of colonization in this country, rather than the inherent embedding of colonizing practices in contemporary health and human service institutions

The focus is on the individual and personal, rather than the historical and institutional nature of such individual and personal contexts.

the health and cultural wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within mainstream health care settings warrant special attention. Cultural Respect is the: recognition, protection and continual advancement of the inherent rights, cultures and tradition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. …. [it] is about shared respect ….[and] is achieved when the health system is a safe environment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and where cultural differences are respected. It is commitment to the principle that the construct and provision of services offered by the Australian health care system will not compromise the legitimate cultural rights, values and expectations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The goal is to uphold the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to maintain, protect and develop their culture and achieve equitable health outcomes.

Knowledge and awareness, where the focus is on understandings and awareness of history, experience, cultures and rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.A focus on changed behaviour and practice to that which is culturally appropriate. Education and training and robust performance management processes are strategies to encourage good practice and culturally appropriate behavior.Strong relationships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, and the health agencies providing services to them. Here the focus is on the business practices of the organization to ensure they uphold and secure the cultural rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.Equity of outcomes for individuals and communities. Strategies include ensuring feedback on relevant key performance indicators and targets at all levels.

commitment to the principle that the construct and provision of services offered by the health system will not compromise the legitimate cultural rights, values and expectations of Aboriginal people. It is a recognition, appreciation and response to the impact of cultural diversity on the utilisation and provision of effective clinical care, public health and health system administration

The term ‘Cultural competence’ originates from Transcultural Nursing developed by Madeleine Leininger. Borrowing from anthropology, the aim was to develop a model that encouraged nurses to study and understand cultures other than their own. You can read my paper on the complementariness of cultural safety and competence here. Wellness for all: the possibilities of cultural safety and cultural competence in New Zealand. Betancourt, et al., 2002, p. v define it as:

the ability of systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs and behaviours, including tailoring delivery to meet patients’ social, cultural and linguistic needs

Dr Tom Calma’s (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commissioner ) Social Justice Report 2005 instigated a human rights-based approach Campaign to close the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (up to 17 years less than other Australians at the time). This report called on all Australian governments to commit to achieving equality of health status and life expectancy within a generation (by 2030).

A coalition drawn from Indigenous and non-Indigenous health and human rights organisations formed the Close the Gap Campaign, which was launched in April 2007 by Catherine Freeman and Ian Thorpe, the Campaign’s Patrons. The CTG Campaign is currently Co-Chaired by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Mick Gooda and Co- Chair of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, Kirstie Parker. The Campaign Steering Committee is comprised of 32 health and human rights organisations. The members of the Campaign Steering Committee have worked collaboratively for approximately nine years to address Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health inequality through two primary mechanisms: attempting to gain public support of the issue and demanding government action to address it.

http://blogs.crikey.com.au/croakey/2013/08/04/youtube-an-excellent-resource-for-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health/Cultural competence video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpzLzgeL2sADr Tom Calma – Cultural Competency

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tnYuTY0fn3s

http://amptoons.com/blog/files/mcintosh.htmlWhat kind of Asian are you?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWynJkN5HbQReverse racism, Aamer Rahman:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dw_mRaIHb-M

Cite as: DeSouza, Ruth. (2014). One woman’s empowerment is another’s oppression: Korean migrant mothers on giving birth in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. doi: 10.1177/1043659614523472. Download pdf (262KB) DeSouza J Transcult Nurs-2014.

Published online before print on February 28, 2014.

Abstract