When I was a nursing student I remember someone telling me “Nurses care, and Doctors cure”. Apparently, our job was the former, in the biomedical division of labor. I was shocked when I began my clinical experience to find that the health care system did not support care. I mean, nurses attempted to meet people’s needs, but the intensive and intimate labors of caring for the list of patients we were assigned were relentless and it always felt like clock time. Every shift I knew that the minute I walked through the door (particularly when I worked in hospitals) that I would need to completely forget about myself and be present for other people. I needed to meticulously account for my time in increments, scheduling when Person X would get their medication and Person Y would need to have their IV checked, when someone would need their surgical tubes removed, their catheter emptied. Somehow, I also had to show care, concern, respect, warmth in between a multitude of tasks. I’d have to make sure I had lunch at the right time to ensure that others could have their lunch. I often forgot to empty my bladder. This non-stop labor meant that there was little time to also nurture myself or my colleagues. I wondered how it was possible to care for others when there seemed to be no time to care at all. I had nothing to give anyone (let alone myself) after a shift, and thought about how I cared for strangers all day and had nothing left over to care for loved ones. A wise Charge Nurse (that’s you Lyndsay Johnston) moved me to an afternoon shift in my seventh month as a new graduate because she could tell I might burn out. Later after I had worked in community mental health and moved to the perinatal care setting, I was struck by the factory-like induction process into parenthood. The absence of joy and warmth, the tick box processing of parents- to- be through procedures that foregrounded the hospital’s interests of health and safety, but not the transition to parenthood. That’s not to say individual midwives and obstetricians were not kind, but there was something about the way the system was designed that precluded really acknowledging personhood, community and relationality.

I have moved away from clinical practice these days to research and teaching, but I know the advent of electronic health records has reconfigured how work gets done. Some have argued that technology and platforms dictate how care is provided, rather than the recipient of care or their family. While others claim that our technocratic business models are contributing to the loss of hope, and what some call “callous indifference”(Francis, 2013). So, although we come to work in health because we care, something happens to us. We who work in healthcare, we who come to health to make a difference. We, who come with tender hearts as Mimi Niles points out, sometimes end up contributing to a crisis of care in healthcare. This happens to our tender-hearted young quickly, the longer nursing students are in the practice world, the more their capacity to empathise declines. There is evidence of endemic horizontal violence and attrition from the workforce. Putting in place patient-centered care and cultural safety are suggested as ways in which empathy and compassion in health care can be embedded particularly for people for whom these services were never imagined.

How is it possible that harm is done to people while in the ‘care’ of institutions? Serious failings in hospitals and the absence of care (including those at Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Hospital in England) have led to calls for the urgent transformation of health services. Two inquiries (2013 Francis Report) found that basic elements of care were missed, patients were left in soiled beds, had water placed out of reach and received inadequate support for feeding and other activities. Most recently we’ve had Royal Commissions into aged care, disability, and mental health. Could it be that the failure to care is not exceptional, but instead that poor quality is embedded in the structures and processes of the healthcare system? (Goodwin et al., 2018). Not only hospital-acquired infections or surgical errors or medication errors, but also neglect and missed (where an aspect of required patient care is omitted or delayed) care? (Kalisch, Landstrom, & Hinshaw, 2009). How do we strike a careful balance between thinking about the failure to care as a systems-level issue, while also thinking about health professionals as individuals who are a part of systems? (Tierney et al. 2019). We are a profession that cares and we take caring very seriously, but how can we care when caring itself is marginalised? How can we care for those who are marginalised when we ourselves might feel marginalised and unresourced, when we feel overwhelmed? I think unless we seriously think about these questions, we are at risk of reproducing exclusionary practices and unsafe care.

This leads me to the purpose of this blog. Thinking about an experience of caring and being cared for. My portrait is being exhibited at the Being Human exhibition at Wellcome Collection in London, as a part of the No Human Being is Illegal (In All Our Glory) artwork. It’s one of two life-sized nude photographic portraits going on display for a year from a participatory collage work (see the write-up by Tania Leimbach in the Conversation) made for the controversial 19th Biennale of Sydney (2014) ‘You Imagine What You Desire’. 28 Australian and international artists led by Matt Kiem (in response to a call by refugee and ex-detainee organisation RISE) wrote an open letter to the Board asking them to abandon major funder of 41 years, Transfield, who were complicit in Australia’s brutal asylum deterrence and indefinite detention regime. The Board were also invited to engage in further discussion about other sources of ethical funding. There is of course much more to say about the ‘boycott’ which you can read on the xBorder blog and xBorder Working Paper by Angela Mitropoulos, Guardian article by Alana Lentin and Javed de Costa or this piece from Danny Butt and Rachel O’Reilly about art and detention abolition.

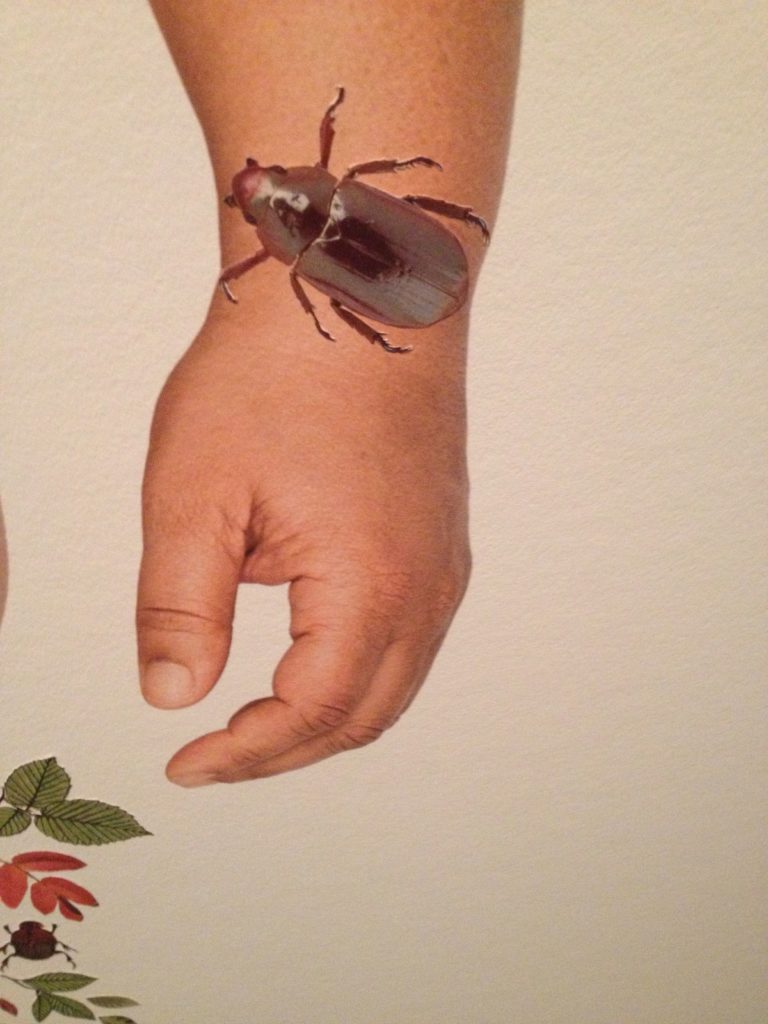

I learned a lot from the amazing collective process for the No Human Being is Illegal (In All Our Glory) artwork. I was one of 20 subjects chosen out of 279 people who volunteered themselves as subjects. 50-70 collage participants took part in the intensive collage workshops (thrice-weekly workshops for nine months) to make the portraits. Participants chose materials from Deborah’s extensive library of resources, including books, encyclopedias, reference materials, magazines to make a collage portrait that reflected the subjects’ interests. I was able to share my writing and theoretical and political commitments and actually visit the workshop setting in Sydney to talk to the participants. This project embodied care from conception. Collective decisions were made and I was asked for consent every step of the way, with every iteration of the process, with every travelling exhibit.

Having traveled around New South Wales, Queensland and VIC, it has now made its way to London and is a part of the Wellcome Collection. Wellcome is a global charitable foundation with a free museum and library that encourages “new ways of thinking about health by connecting science, medicine, life and art”. Deborah Kelly the artist who was commissioned for the work is based in Sydney. Her works have been shown around Australia, and in the Singapore, Sydney, TarraWarra, and Venice Biennales. You can read more of her extensive biography here. You can also support her latest work by purchasing a set of holy cards The glorious Liturgy of the Saprophyte by SJNorman.

Here’s Deborah’s recollection of the process of making the work (you can also listen to Deborah’s beautiful voice by clicking on this link:

I do want to say, I feel like that the care with which the work was made, the work is constituted by that care. It’s not an add on. That’s what the work is. Your portrait is extremely complex. You came and talked to us and people all took notes. You actually came to the studio, right? Where we were working…and everybody took notes, but everybody’s notes were different. And so we really, really struggled over how to reconcile them. And then we realized we didn’t have to reconcile them. In fact more is more so we can, we could just do everything. Yes, so that’s why it ended up being so abundant, because we were trying to represent as much as we could of what you told us, which is pretty exciting. So the bubbles around you represent both ocean effervescence and champagne.

And inside the bubbles, images that represent various of the things you told us. So inside one of the bubbles is a very cute image of a man and a woman in a typically romantic situation. And that was to honor your relationship with Danny. Yeah, and there’s stuff that represents your life as a nurse, your life, as a nurse in maternal health, your early life in Africa. I think we even represent the car accident somewhere in a quite lateral way. Your relationship with the Catholic church. So the bubbles are all full of all different aspects of things that you told us, but the actual portrait of you, was our interpretation of your own effervescence, body pride, sexiness, love of adornment and color.

So that’s what we were doing, we weren’t hiding you. We were celebrating you. So some people like my Dad, for instance, we were hiding him, and making him modest, a few people needed to be modest. But we wanted to make yours a portrait of glorious shamelessness. And remember you left your leg hair unshaven for us . And we really, really loved that. That’s why there’s nothing covering your legs.

You’ll remember we gave you twinkle toes and all of those shells come from Arthur Henry Mee (1875-1943). A very beautiful children’s encyclopedia from the 1930s. They’re printed on this very old fashioned clay coated paper, which is incredibly durable, which is why they’re a hundred years old, but they are still very beautiful in color.

Then we gave you that cloak of leaves, to represent you in the natural world. As a kind of queen, and we gave you that pubic tiara, and that was a nod to queenlinness, and adornment for shamelessness. Although we realized once we’d cut out those thousands of leaves, what a giant task we had set ourselves. On the day we finished, people stood on chairs, cheering themselves.

We also gave you some jewelry made out of gold and silver beetles, these were cut out with extraordinary finesse by XXX who hadn’t done collage before, but turned out to be a person of unbelievably fine motor skills. And he was very, very proud of working on that portrait

I really remember all the people in the workshop, who couldn’t bear to be photographed in the nude, saying, oh, I wish this was me. Everybody was like, oh my God. It’s like, we’re just giving this person a big long cuddle!

I’m finishing off this blogpost, reflecting on the challenging year 2021 has been for most people, with uncertain times still ahead, putting the concern with care front and centre. To me, care has an element of attunement or engagement, of generosity. Nurse ethicist Joan Tronto (1993) defines care as: “a species activity that includes everything we do to maintain, continue and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible. That world includes our bodies, our selves, and our environment, all of which we seek to interweave in a complex, life-sustaining web’ (p. 103). Tronto sees care as a practice that requires attentiveness, responsibility, competence and responsiveness. It involves caring about, caring for, caregiving and care receiving. The inclusion of the latter recognises that at some point we might also be vulnerable and require care. it’s been a lifetime inquiry for me, the question of how can we be invigorated or returned to caring? In my dreams I wish everyone that we cared for, felt secure, cared for and loved. Yet, this isn’t an individual task, it is collective. Feminist academic Alison Mountz and colleagues (2015, p.1239) frame care as warfare in the tradition of Audre Lorde and Sara Ahmed. That is: “cultivating space to care for ourselves, our colleagues, and our students is, in fact, a political activity when we are situated in institutions that devalue and militate against such relations and practices”. In academia, as our summer break approaches here in the Antipodes, I am inspired by the words of Ali Black and Rachael Dwyer (2021, p.9) who talk of their collective work and write “We are fuelling our creative and collective capacities in ways that are expansive, collaborative, pleasurable, and collectively advantageous”. I wish at this seasonal time of contemplation and rest, that this invitation to collectively flourish activates all those who care about, care for, give care and receive care. Rather like I was fed during the making of an exquisite collage work by Deborah Kelly and participants.